Railroads In The 20th Century (1900s): Facts, Statistics, History

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

By 1900, the country's total rail mileage had increased to 193,346, from 163,597 in 1890. It would continue to grow for another decade before reaching its all-time high during the World War I era.

At the 20th century's dawn, railroads had reached their economic supremacy; it seemed rails poked into the tiniest of hamlets and trains dominated American commerce in every possible way.

This resulted in a minority group of very rich and influential individuals; names like Cornelius Vanderbilt (and his heirs), Edward Harriman, Jay Gould, James Hill, and Collis P. Huntington.

By the late 19th century the federal government had grown weary of their power and sought to reel in the industry. That effort began in 1887 with the Interstate Commerce Commission's creation, tasked with regulating the railroads.

History

It continued with 1893's Railway Safety Appliance Act, forcing railroads to install the automatic air brake and knuckle coupler on all equipment. Between 1900 and 1910 a series of additional acts were passed to further tighten the government's grip.

From a statistical standpoint, the new century's first twenty years were the industry's zenith in terms of size and scope; after 1920 traffic and corridors were slowly lost to other transportation modes (accelerated by the depression).

Photos

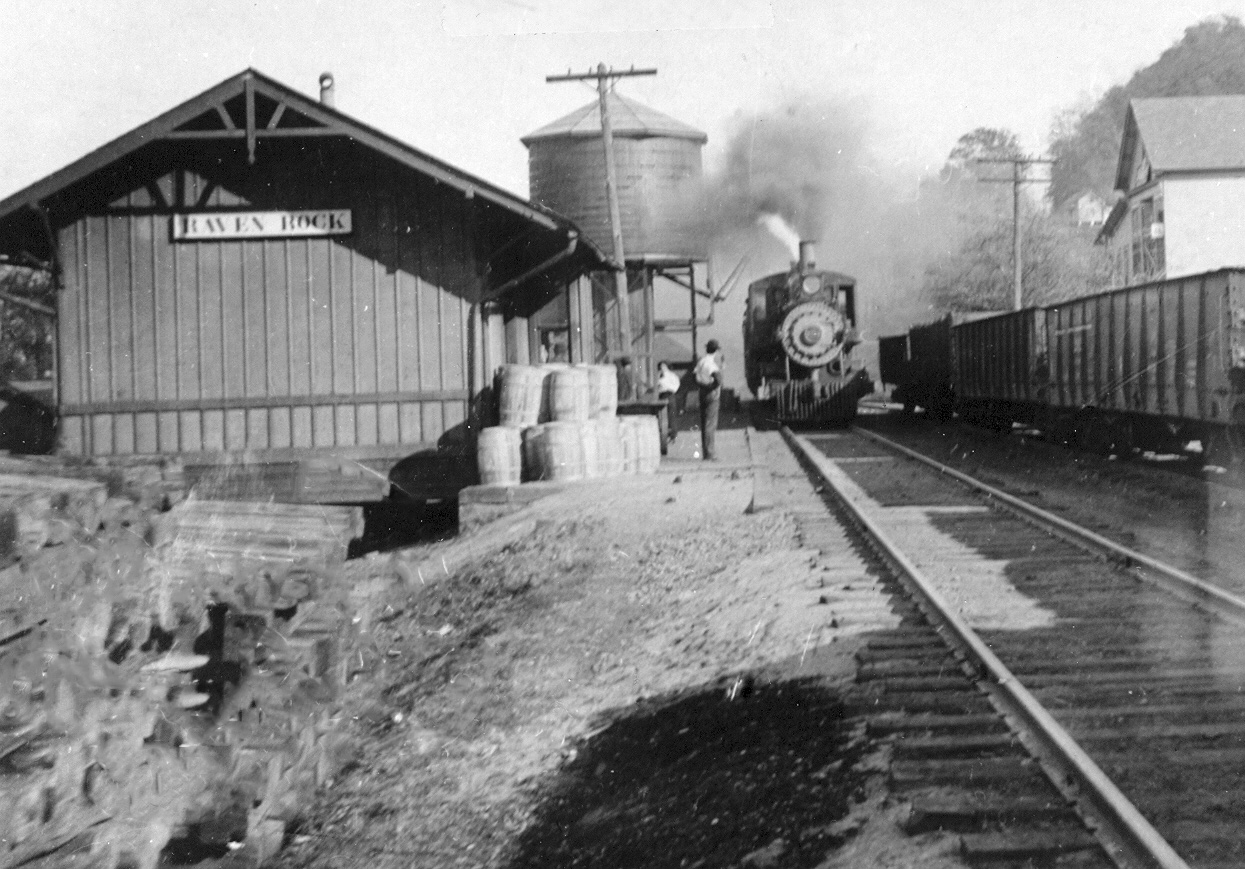

A local Baltimore & Ohio train makes a stop at the small Raven Rock, West Virginia depot and water tank during the early 1900s. Today, the tracks remain in use by CSX but everything else in this scene is long gone. Author's collection.

A local Baltimore & Ohio train makes a stop at the small Raven Rock, West Virginia depot and water tank during the early 1900s. Today, the tracks remain in use by CSX but everything else in this scene is long gone. Author's collection.Significance

While the national rail network did not reach its all-time peak until 1916, the industry's power was largely capped during the 20th century's first decade.

As historian John Stover notes in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," President Theodore Roosevelt (sworn in on September 14, 1901 following President William McKinley's assassination by Leon Czolgosz) was no fan of their intimidation and dominance. Wishing to change this, he oversaw sweeping legislation during his administration.

In retrospect, perhaps his efforts were too sweeping although they did prove effective. There were two noteworthy bills passed into law at this time, the Elkins Act of 1903 and Hepburn Act of 1906; both brought increased regulation and significantly broadened the Interstate Commerce Commission's (ICC) power.

The former ended the use of rebates in an effort to protect competition and fair pricing. The latter amended its predecessor by providing the ICC broad powers in controlling freight rates. Essentially, railroads were banned from adjusting rates without prior approval.

At A Glance

2,107 Miles (1900) | |

Elkins Act (1903) Hepburn Act (1906) Mann-Elkins Act (1910) |

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- DeNevi, Don. America's Fighting Railroads, A World War II Pictorial History. Missoula: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1996.

- Hilton, George and Due, John. Electric Interurban Railways in America, The. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

In 1910, new president William Howard Taft expanded upon Roosevelt's efforts. He held an even worse view of railroads, overseeing passage of the Mann-Elkins Act. This legislation further increased the ICC's power, requiring railroads to show just cause for any rate hike.

Unfortunately, such draconian measures were not lifted until 1980 (Staggers Act), by which time many companies had either declared bankruptcy or were in the process of doing so. (A strong argument could be made against these policies, which ultimately led to the industry's downfall by the 1970's and abandonment of so much infrastructure.)

Perhaps the decade's greatest improvement was the transformation from iron to steel rails. Steel's durability and strength could simply not be matched; the nation's first mill appeared in the 1860's and steel became so widespread by 1900 that virtually all lines boasted such.

The record mileage achieved in 1916 (254,037 miles) could rightfully be argued as the industry's apex in many other ways. For instance, additional regulations and other transportation modes would increasingly curtail its market power beyond the 1920's.

Interurban Construction

The interurban story has been well documented and more information regarding this fascinating aspect of American transportation can be found here.

For a complete history I would strongly recommend a copy of Dr. George Hilton and John Due's authoritative piece, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," which thoroughly covers the subject.

The interurbans sprang up in the very late 19th century as an early form of rapid transit utilizing electrification.

Many saw it as the future in short and intermediate commuter service due to its cleanliness and high speed capabilities.

There were three great periods of interurban development; the first occurred during the 1890's and then reached a great flurry of construction between 1901 and 1904 when more than 5,000 miles were built.

The Panic of 1903 temporarily slowed construction but it reignited during a brief four-year period from 1905 to 1908 when another 4,000 miles were placed into service. Another financial setback in 1907 all but ended further investment except in isolated pockets.

In 1889 there were just 7 miles of interurbans in use, a number which jumped to 3,122 by 1901, and finally peaked at 15,580 in 1916.

As Dr.'s Due and Hilton point out, "...by 1912 the American interurban network on the whole had taken its final shape. A marked decline set in about 1918, and in the decade 1928-1937 the industry was virtually annihilated. By 1960, no trace of it remained in its original form."

It's immediate downfall began with the early automobile's success (notably Henry Ford's Model T), which were affordable for everyday Americans despite poor road conditions, and the Great Depression which began with 1929's stock market crash. In truth, interurbans should have never been built.

The systems were designed to link nearby cities and act as high speed, commuter operations that would compete against traditional steam railroads. Unfortunately, many were never engineered properly for such speeds, featuring steep grades and sharp curves.

Most were further handicapped by choosing rights-of-way along public roads and through city streets in an effort to reduce construction costs.

In a market where profits were slim, only those built to better standards with an eye towards freight lasted beyond World War II. Even famous systems like the Pacific Electric Railway and Chicago, Aurora & Elgin barely survived into the 1950's.

Those which remained after 1960, like the Illinois Terminal, did so as freight carriers, having shed virtually all of their interurban heritage.

The United States' entry into World War I (April 6, 1917) also proved incredibly problematic; most railroads were completely unprepared for the tsunami of traffic that followed.

Not only did freight yards jam and trains snarl to a crawl but many carriers also lacked sufficient equipment to deal with the deluge.

In an effort to maintain fluid traffic, the federal government took the unprecedented step of nationalizing the industry on December 28, 1917 via the United States Railroad Administration (USRA). While railroads were paid rental fees, the USRA was nevertheless very hard on their property.

Interested only in maintaining orderly and methodical operations, corridors were strained under the relentless traffic and deferred maintenance. In addition, passenger trains deemed unnecessary were eliminated, shops and terminals were centralized, and profits generally ignored.

On March 1, 1920 the network returned to private ownership. Unfortunately, companies were forced to spend heavily in repairing the damage. The industry worked hard to prevent a future USRA takeover and was well-prepared when the country entered World War II in 1941.

Despite the heavy-handed measures, some positives did come from USRA control, such as standardized locomotives (Notably the 4-8-2 "Light Mountain," 2-8-2 "Light Mikado," and 4-6-2 "Pacific." This practice became common during the diesel era.) and rolling stock.

A scene from Baltimore & Ohio's Low Yard in Parkersburg, West Virginia circa 1915. Author's collection.

A scene from Baltimore & Ohio's Low Yard in Parkersburg, West Virginia circa 1915. Author's collection.After 1920, many things changed; coupled with increased regulation, new competition (automobiles and the airplane) eroded railroads' dominance. The Ford Model-T, at less than $300, proved an affordable option for many Americans.

In spite of poor road conditions, millions were sold through the 1920's while the U.S. witnessed its first commercial flight by Elliot Air Service via a Curtiss JN 4 aircraft in 1915.

The so-called "Roarin' Twenties" were a great economic boon where the nation's wealth doubled between 1920-1929 and the country became a consumer society that continues through today.

Unfortunately, the quick spike in wealth led to financial collapse following the stock market crash of October 28, 1929.

The ensuing depression was as difficult on railroads as every day Americans; many either fell into receivership or were outright purchased by stronger carriers. It also effectively wiped out the interurban industry.

In an effort to combat these effects and regain market share Union Pacific, Pullman, and the Winton Engine Company teamed up to unveil a radical new concept, the streamliner, in 1934.

The train was colorful, fast, and comfortable, a profound departure from what the public had always known. Shortly thereafter, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Budd Company showcased a similar train shrouded in stainless steel.

Rail Travel In The "Golden Age"

Sleek, fast, and ultra-modern, the Pioneer Zephyr broke the speed record between Denver and Chicago, covering the 1,000+ miles, non-stop, in only 13 hours, 5 minutes. This train and the M-10000 paved the way for a future generation of rail travel.

No longer would trains be drab and colorless; through the World War II era, and beyond, most railroads featured services with some type of streamlining concept incorporated.

The early 20th century is generally regarded as railroads' "Golden Age" with several famous trains, stations/terminals, and other noteworthy landmark feats dotting the American landscape.

It was certainly a different era in America when nearly everyone was exposed to railroads in some manner (not so today). By 1900, rail equipment was quite specialized with comfort and luxury commonplace. In addition, iron, and then steel, replaced wood as the primary component with which cars were built.

A Baltimore & Ohio passenger train is loaded with mail and luggage at New Martinsville, West Virginia in a scene dating to the 1940s. Passenger service on the Ohio River Branch would end the following decade. Author's collection.

A Baltimore & Ohio passenger train is loaded with mail and luggage at New Martinsville, West Virginia in a scene dating to the 1940s. Passenger service on the Ohio River Branch would end the following decade. Author's collection.In his excellent book, "The Railroad Passenger Car," author August Mencken notes as far back as 1846 H.L. Lewis proposed building cars of iron, claiming they would be of lighter weight and greater strength.

The first car constructed entirely of iron was the so-called "LaMothe Car," patented by Dr. B.J. LaMothe in 1854.

The initial example, at 46-feet in length, debuted in 1859 and tested on several railroads the following year. As the 19th century progressed, iron transitioned to steel and by the early 1900's many railroads were operating cars built partially or entirely of metal.

This led to the so-called "heavyweight" designs (the name derived from the considerable weight) which found widespread use until lightweight alloys (like aluminum) grew in popularity during the 1930's.

George Pullman and his Pullman Palace Car Company (later reorganized as the Pullman Car Company) began building cars in 1867 and was the premier manufacturer by 1900, having acquired all other competitors by then; nearly every top train carried at least some Pullman equipment.

The company's plant was located in Pullman, Illinois and its cars were unmatched in comfort and style. If you traveled by rail prior to the 1960's, Pullman was the name you trusted.

While most famous for sleepers, it built other types such as parlors, diners, and domes. It also manufactured freight cars and even self-propelled rail cars ("Doodlebugs").

Notable Trains

From a historical standpoint, many of the best-remember trains appeared during the early 20th century such as:

- Pennsylvania's Broadway Limited (1912)

- New York Central's 20th Century Limited (1902)

- Santa Fe’s Chief and Super Chief (1926 and 1936), Baltimore & Ohio’s Capitol Limited (1923)

- The jointly operated California Zephyr (Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; Denver & Rio Grande Zephyr; and Western Pacific) of 1949

- Milwaukee Road’s legendary Hiawathas (inaugurated in 1935)

- Great Northern’s venerable Empire Builder (1929)

- Southern Pacific’s Daylights (launched in 1922)

- Southern Railway’s Crescent Limited (1922)

The nation's largest and most renowned passenger stations also appeared during the industry's "Golden Age."

Baltimore & Ohio 4-6-2 #5133 (P-3) hustles a southbound passenger train from Pittsburgh to Parkersburg, West Virginia near Wheeling/Benwood (WV) in a scene likely dating to the 1930s or 1940s. Author's collection.

Baltimore & Ohio 4-6-2 #5133 (P-3) hustles a southbound passenger train from Pittsburgh to Parkersburg, West Virginia near Wheeling/Benwood (WV) in a scene likely dating to the 1930s or 1940s. Author's collection.Renowned Terminals

Some of these include:

- Pennsylvania Station (1910)

- New York Central’s Grand Central Terminal (opened in 1913, replacing Grand Central Station)

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western's Hoboken Terminal (1907)

- The jointly built and operated [Union Pacific, Santa Fe, and Southern Pacific] Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal (today's Los Angeles Union Station)

- Chicago Union Station (1925)

- Denver Union Station (1914).

Sadly, many, like Pennsylvania Station, have since been partially or entirely razed.

The period through World War I also signaled railroading's peak dominance in transportation; during this time they hauled an astonishing 98% of intercity passenger traffic and 77% of intercity freight traffic.

However, following the Second World War passenger traffic declined significantly and would not recover, even as railroads spent heavily on new equipment through the 1950's.

In the 1960s, many were trying desperately to end or curtail services. Coupled with the stifling regulation, Congress finally relented and created the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) in 1971, thus enabling most railroads to exit the passenger business.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

New Jersey - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 27, 25 09:57 AM

If you're seeking a unique outing or a memorable way to celebrate a special occasion, wine tasting train rides in New Jersey offer an experience unlike any other. -

Missouri - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 27, 25 09:51 AM

The fusion of scenic vistas, historical charm, and exquisite wines is beautifully encapsulated in Missouri's wine tasting train experiences. -

Minnesota - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 27, 25 09:48 AM

This article takes you on a journey through Minnesota's wine tasting trains, offering a unique perspective on this novel adventure.