Railroads And The Industrial Revolution (1850s)

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The 1850s were a defining decade in American railroading as scattered systems became an organized and fluid interstate system.

What began in the 1820s as local ventures, serving a specific purpose, had transformed into an indispensable transportation network by 1850. At that time there were a total of 9,022 miles in active service.

This number had more than tripled by 1860 to 30,000+ and would continue to rapidly increase over the following two decades (despite severe financial panics in 1857 and 1873).

The decade also witnessed technological advancements in communication, traveling accommodations, more powerful locomotives, heavier freight cars, and overall speeds.

History

The latter had improved to the point that one could reach Chicago from New York in just two days. At the turn of the 19th century, such a trip had taken more than a month!

The 1850s also saw railroads reach across the Mississippi River, serve parts of Texas, and lay down roots in California. By this point in America railroads had blossomed into the driving force behind America's Industrial Revolution.

Images

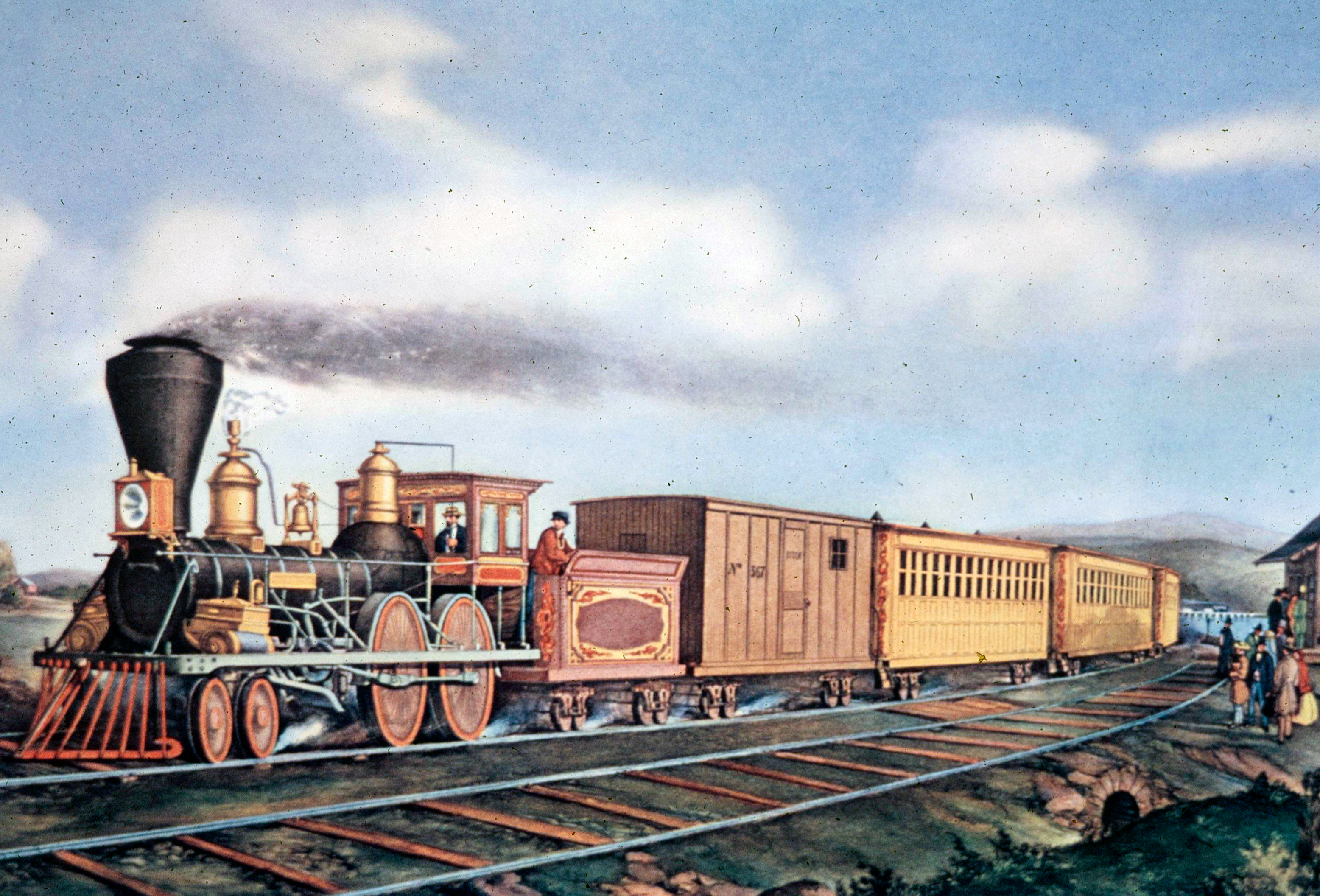

A Currier & Ives lithograph by Nathaniel Currier featuring an express train in 1855. Author's collection.

A Currier & Ives lithograph by Nathaniel Currier featuring an express train in 1855. Author's collection.Industrial Revolution

As the iron horse reached increasingly critical needs, the federal government made plans to complete a transcontinental route to the Golden State.

The book "Railroads In The Days Of Steam" by Albert L. McCready and Lawrence W. Sagle, notes that investors had spent some $372 million on railroads in 1850.

In his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," John Stover points out this number had skyrocketed to $1.15 billion by 1860. Almost single-handedly railroads transformed the United States into a world power.

The 1850s not only established railroads as the preeminent mode of travel but also witnessed a flurry of new construction.

While future decades witnessed greater mileage (notably the 1880's) the 1850s demonstrated the iron horse's remarkable abilities to transport considerable freight and passengers at previously unheard of speeds.

Perhaps Mr. Stover stated it best: "By the mid-fifties the United States, with no more than 5 percent of the world's population, had nearly as much rail mileage as the rest of the world...Few other institutions in the country did business on so vast a scale or financed themselves in such a variety of ways."

This sentiment is confirmed in the book, "The First Tycoon: The Epic Life Of Cornelius Vanderbilt," by T.J. Stiles as he articulates how railroads were the first large corporations, employing thousands and capitalized in millions.

Another major achievement reached at this time was the first use of telegraph in 1851 to control train movements.

This new system allowed railroads near instant communication, in coded dots and dashes, and spurred the construction of line-side poles, which became a common sight along nearly every rail line through the 1980's (by then used primarily for signaling purposes).

Finally, most of the now widely-regarded tycoons were involved with railroads by the 1850s; names, like Vanderbilt, Collis P. Huntington, and Jay Gould. These individuals, and others, oversaw most of the new construction which took place through the latter 19th century.

Heading West

Even the government was becoming involved as the iron horse became a vital means of transportation. By the mid-1850's, the United Stats controlled virtually all of central North America from the Atlantic to Pacific coast.

Because of this, leaders in Washington recognized a fast and efficient means of transportation was needed. This was furthered by California achieving statehood on September 9, 1850.

While the "Gold Rush" brought tens of thousands of prospectors across its borders, it was rich farmland within the San Joaquin Valley, and seaside ports (totaling 840 miles), that transformed California into the country's most successful economy.

The state's involvement with the iron horse predated the Transcontinental Railroad by more than a decade.

The Sacramento Valley Railroad is identified as its first, filing articles of incorporation as a common-carrier on August 4, 1852.

California's very first railroad actually put into operation was the Arcata & Mad River Railroad, established in 1854 and opened later that year. It was built by private interests to load lumber schooners in Humboldt Bay near Arcata.

Statistics

9,021 Miles (1850) 31,246 (1861) | |

$372 million (1850) $1 billion (1860) | |

$39,000 (New England) $46,000 (Mid-Atlantic) $24,000 (South) Former Northwest Territory ($30,000) |

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

According to the book, "The Northern Pacific, Main Street Of The Northwest: A Pictorial History" by author and historian Charles R. Wood in the spring of 1853 Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (who later became president of the Confederate States of America) initiated the task of surveying western routes to the Pacific Coast.

There were eight options put forth running along various, north-to-south parallels. Due to the ongoing issue of slavery Congress could not agree on which.

As a result, the entire undertaking remained dormant for years. As tensions between northern and southern states grew it reached a crescendo when Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860.

Only weeks later, South Carolina formally seceded from the Union (December 20, 1860); soon afterwards several other states followed, Confederate forces opened fire on federal troops stationed inside Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, and the Civil War officially began.

With the nation's fracturing, northern leaders settled on the central option although its construction did not begin until 1862 and was not finished until May 10, 1869.

In spite of this, the 1850s did witness one successful endeavor; the federal government bequeathed large tracts of lands to railroads.

It was all in an effort to build and develop new areas west of the Mississippi River and the Great Plains. These regions became home to many of the now-classic granger lines like the Rock Island, Milwaukee Road, Burlington, and Chicago Great Western.

Another fascinating lithograph from Currier & Ives, also done by Nathaniel Currier, featuring Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1857. Note the Baltimore & Ohio train heading east over the Potomac River. You can also just make out the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal in the foreground. Compare this scene to modern day photos of Harpers Ferry. Author's collection.

Another fascinating lithograph from Currier & Ives, also done by Nathaniel Currier, featuring Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1857. Note the Baltimore & Ohio train heading east over the Potomac River. You can also just make out the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal in the foreground. Compare this scene to modern day photos of Harpers Ferry. Author's collection.Reaching Buffalo and the Ohio River

Two of the 1850's most significant corporate developments was the original New York Central Railroad's formation on May 17, 1853 and the Erie Railroad's completion in the spring of 1851.

The former opened a through route from Albany to Buffalo and later became part of Vanderbilt's New York Central & Hudson River Railroad connecting New York with Chicago.

The latter opened its original main line between Piermont and Buffalo, New York in 1853. The Erie was the jewel of New York and the only railroad at that time to boast a route of its length under common ownership.

In later years the company finished a through corridor from New York to Chicago, acting as the smallest as the four major eastern trunk lines.

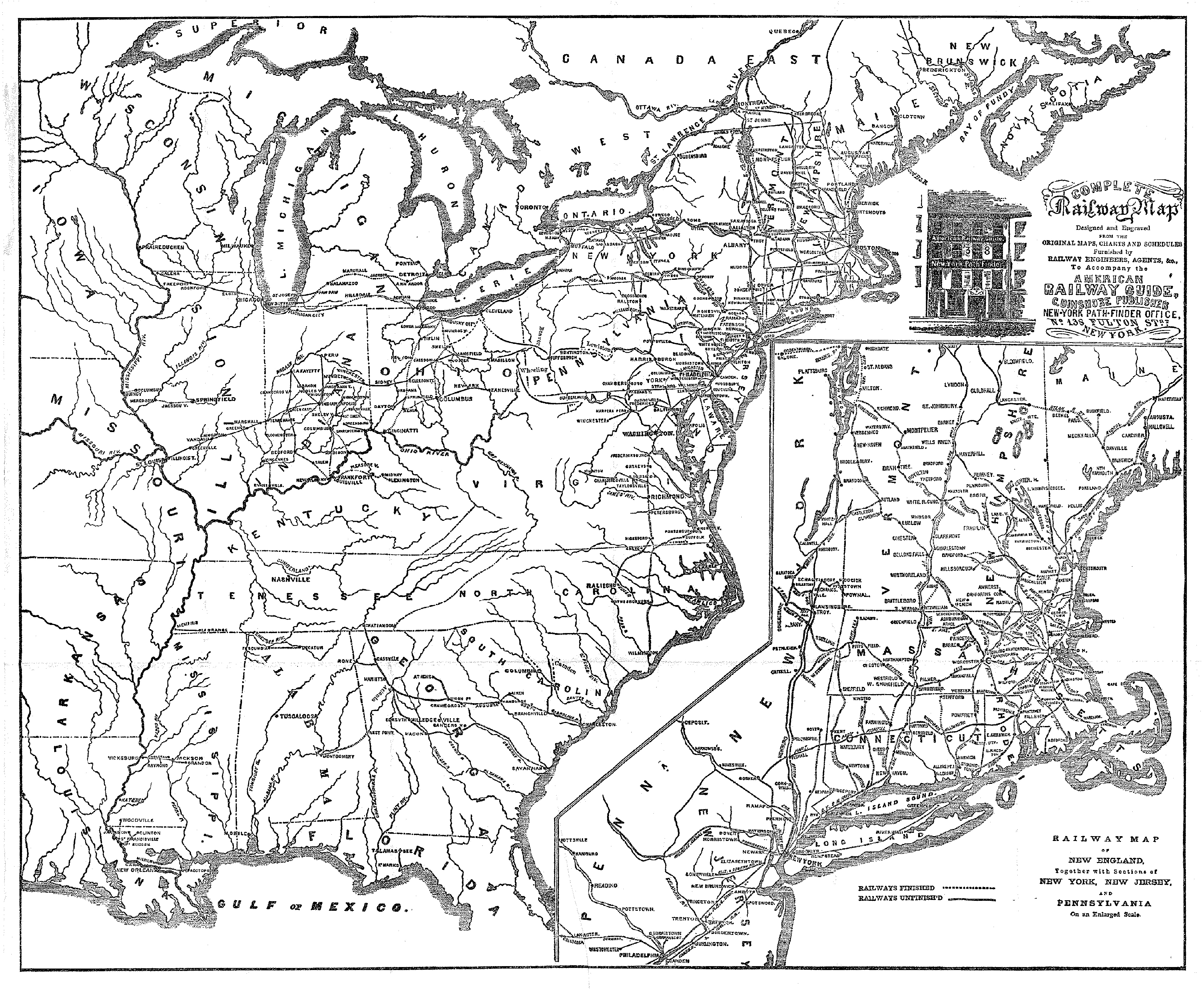

National Railroad Map (1851)

The other two noteworthy systems, the Baltimore & Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroads continued their push westward past the Ohio River. As this was ongoing, Chicago was fast becoming the "central hub" of the industry, then-served by 11 railroads.

Around the Mississippi River the Illinois Central completed its so-called 705-mile "Charter Lines" on September 27, 1856.

This corridor formed a rough "Y"; the main line would head north from Cairo, Illinois, pass through Clinton, and reach Freeport before turning west and terminating at Dunleith (East Dubuque) along the Mississippi River. It would span a total of 453 miles.

In addition, a so-called branch would track due north from a point which later became Centralia (incorporated in 1859 it is named for the point where IC's Charter Lines converge) and reach Chicago, totaling 252 miles

George Pullman

Also, in 1859 George Pullman completed his first sleeping car. The company he later founded would blossom into the most successful and well-known passenger car manufacturer of all-time.

The book, "The Cars Of Pullman" by authors Joe Welsh, Bill Howes, and Kevin Holland note that it was named "Old #9" and was rebuilt from a former day coach. The car was 40 feet in length, featuring 10 upper and 10 lower berths containing mattresses and sheets but no sheets.

It also boasted a small toilet, wash basin, wood-stove for heating purposes, and candles for lighting. While rudimentary by later standards it was quite revolutionary for the time. Railroads in the 1850s also saw a major shift in traffic flow.

Before trains became a reliable means of transportation the fastest way to move people and goods was via the water. For this traffic to move from the East to Midwest required the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers which flowed in a predominantly southern direction, eventually reaching New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico.

With railroads building directly westward into Ohio, Indiana and Illinois traffic could flow directly east-west with Chicago fast become the terminating western hub because of its location along Lake Michigan.

"The Railroad Suspension Bridge." This lithograph, completed by Nathaniel Currier in 1856, features the suspension bridge in Niagara Falls, New York. It was 825 feet in length and just over 2 miles downstream from Niagara Falls, where it connected Niagara Falls, Ontario to Niagara Falls, New York. It remained in use from 1855-1897. American-Rails.com collection.

"The Railroad Suspension Bridge." This lithograph, completed by Nathaniel Currier in 1856, features the suspension bridge in Niagara Falls, New York. It was 825 feet in length and just over 2 miles downstream from Niagara Falls, where it connected Niagara Falls, Ontario to Niagara Falls, New York. It remained in use from 1855-1897. American-Rails.com collection.The city also was the ideal northern terminating point for railroads built north-south such as the Illinois Central and after the western railroads opened they chose Chicago as their eastern terminating hub since so many railroads already served the city and interchanged people and goods there.

Railroads in the 1850s and the expansion that took place during the decade set the stage for what would transpire during the Civil War and how the campaign played out.

The North would hold a commanding advantage in the war not only because most of the country's industrial base was centered in the Northeast but also because most of the railroads with most of the trackage centered in the Northeast and Midwest.

Aside from the war other factors that were becoming issues at that time included different track gauges affecting traffic interchange and the limited number of bridges crossing major waterways.