Northern Pacific Railway: Map, Logo, History, Rosters

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Northern Pacific Railway is often overshadowed by the Transcontinental Railroad. The latter was completed by the Union Pacific (UP) and Central Pacific (CP) in 1869, running the 42nd parallel between Omaha, Nebraska Territory and Sacramento, California.

It offered the West its first efficient means of transportation for greater economic opportunities. For all the Transcontinental Railroad's accolades, the NP carried its own great story. It undertook a similar endeavor to reach the Pacific Northwest but did so without the aid of federal loans.

At first, it appeared the railroad would be built without difficulty as noted banker Jay Cooke secured several million dollars in financing. However, fortunes soon turned and the NP slipped into bankruptcy.

As Northern Pacific languished it seemed unlikely the project would ever be finished. In time, several individuals stepped forward and oversaw its completion, thus establishing the first through route to the Puget Sound.

After 1900, fabled tycoon James J. Hill gained control and the NP joined his so-called "Hill Lines" which included the Great Northern; Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; and subsidiary Spokane, Portland & Seattle.

After numerous attempts the four became one in 1970 when Burlington Northern, Inc. (BNI) was formed. Today, NP's unique Yin Yang herald has vanished but segments of its network remain in service under successor BNSF Railway.

Photos

In this Northern Pacific publicity photo the "North Coast Limited" traverses westbound along the west slope of Bozeman Pass between Gordon and Chestnut, Montana during the 1960's. American-Rails.com collection.

In this Northern Pacific publicity photo the "North Coast Limited" traverses westbound along the west slope of Bozeman Pass between Gordon and Chestnut, Montana during the 1960's. American-Rails.com collection.History

The Northern Pacific is a very old tale involving great hardship and struggle. Many individuals came together in overseeing its completion. Although never celebrated like the Transcontinental Railroad it was nevertheless instrumental in opening another area of the country to new possibilities.

Following its completion along the 49th parallel the states of North Dakota and South Dakota (November 2, 1889), Montana (November 8, 1889), Washington (November 11, 1889), and Idaho (July 3, 1890) all joined the Union. As these former territories were settled and their cities grew, an ever-increasing volume of freight and passengers flowed over Northern Pacific's rails.

At A Glance

Minneapolis/St. Paul - Fargo, North Dakota - Butte, Montana - Tacoma, Washington Logan - Helena - Garrison, Montana Minneapolis/St. Paul - Duluth, Minnesota Staples, Minnesota - Ashland, Wisconsin Little Falls - International Falls, Minnesota Manitoba Junction - Crookston, Minnesota - Winnipeg, Manitoba Wadena, Minnesota - Independence, North Dakota - Jamestown, North Dakota - Leeds, North Dakota Portland, Oregon - Tacoma/Seattle - Bellingham/Sumas, Washington Mandan, North Dakota - Killdeer, North Dakota Mandan - Cannonball, North Dakota Cannonball - Mott, North Dakota |

|

Freight Cars: 34,200 Passenger Cars: 359 | |

Its early years were defined by financial difficulty due to very high construction costs. This endured for nearly two decades until James Hill, the "Empire Builder," acquired control and NP's future was secured. At its zenith it connected the Twin Cities and Duluth/Superior with Spokane, Seattle, Portland, and other western points.

In later years it operated a fine fleet of trains, including the North Coast Limited and Mainstreeter, while also whisking patrons to and from Yellowstone National Park. Interestingly, its immediate heritage can be traced all the way back to another important event in American history, Lewis and Clark's expedition.

The Northern Pacific's route closely followed this fabled journey which departed from St. Louis in May of 1804. The two individuals responsible for the historic endeavor included Captain Merriweather Lewis and Lieutenant William Clark, both Virginians.

According to the book, "The Northern Pacific, Main Street Of The Northwest: A Pictorial History" by author and historian Charles R. Wood, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the men to document newly acquired western lands from France (the Louisiana Purchase) to:

"...explore the Missouri River, and such principal stream as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across the continent for the purpose of commerce."

Logo

They returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806 and while their trek yielded invaluable information, thoughts of a railroad were still decades away.

The first such proposals began in 1853 when then-Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (who later became president of the Confederate States of America) was tasked with surveying routes to the Pacific Coast.

In the end, eight different options put forth running various parallels from north to south. These included the 49th, 47th, 42nd, 41st, 39th, 38th, 35th, and 32nd.

Northern Pacific F7A #6507-A is ahead of train #3, the westbound "Alaskan," as it makes a flag stop at Trout Creek, Montana in May of 1949. On this day the train was carrying an RPO (Railway Post Office), mail/express, coaches, a cafe, and Pullman sleeper. A.E. Bennett photo.

Northern Pacific F7A #6507-A is ahead of train #3, the westbound "Alaskan," as it makes a flag stop at Trout Creek, Montana in May of 1949. On this day the train was carrying an RPO (Railway Post Office), mail/express, coaches, a cafe, and Pullman sleeper. A.E. Bennett photo.Each had its pros and cons although, unfortunately, politics overshadowed everything. Tensions between Northern and Southern states were nearing a crescendo and the ongoing issue of slavery precluded any progress regarding a transcontinental railroad. It all boiled over when Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, a man despised in the South.

Only weeks later, South Carolina formally seceded from the Union (December 20, 1860); several others soon followed, Confederate forces opened fire on federal troops stationed inside Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, and the Civil War was upon the nation.

Formation

With the country in turmoil the North now had the freedom to choose whichever route it wished and settled on the central option along the 42nd parallel. It was not long before stirrings of a second line along a northern trajectory also gained momentum.

These efforts were led by senators from Northern states and, in particular, Josiah Perham, an eastern railroad promoter. Following great effort he secured a rare federal charter for the Northern Pacific Railroad Company. This bill later passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Lincoln on July 2, 1864.

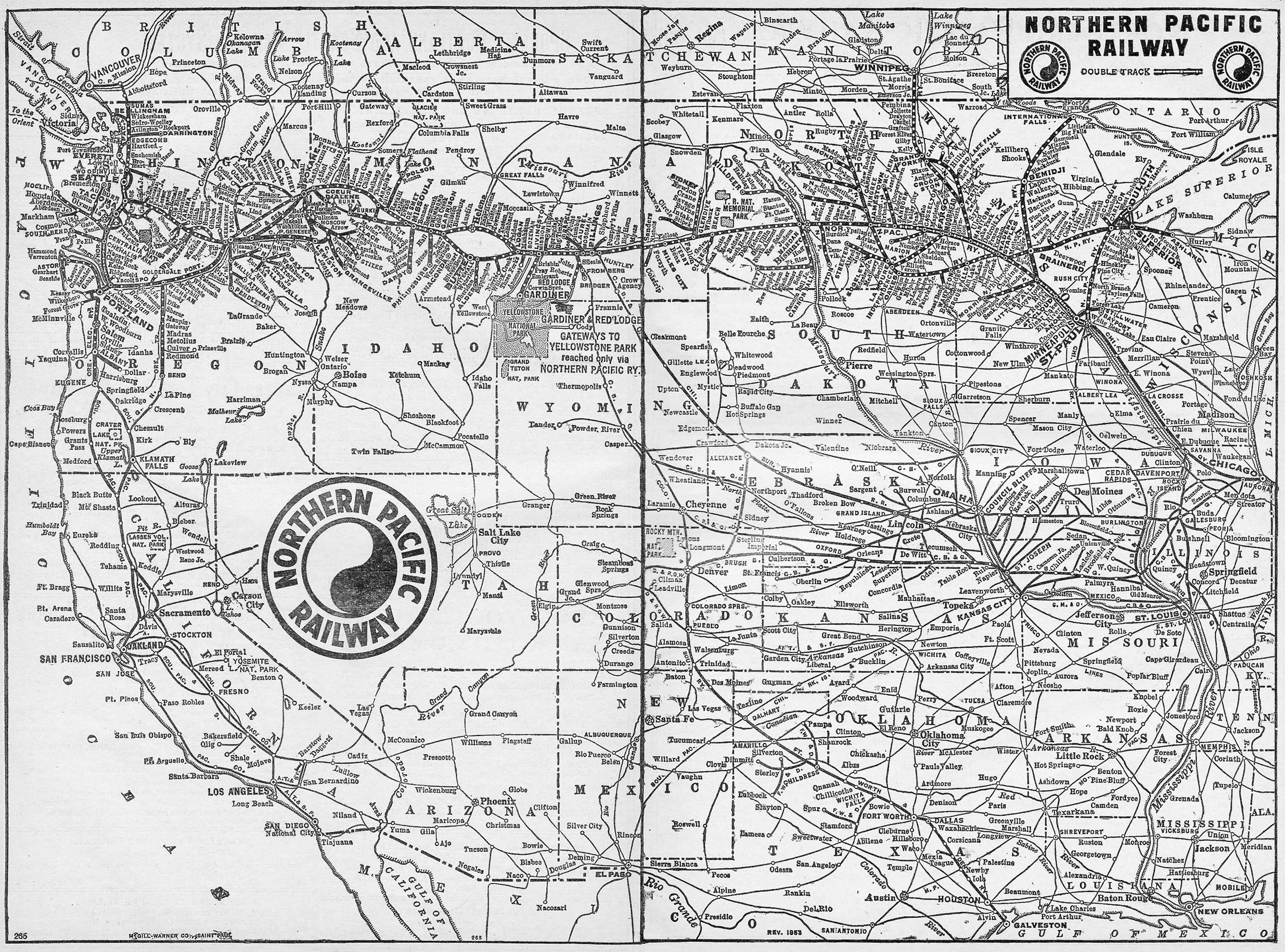

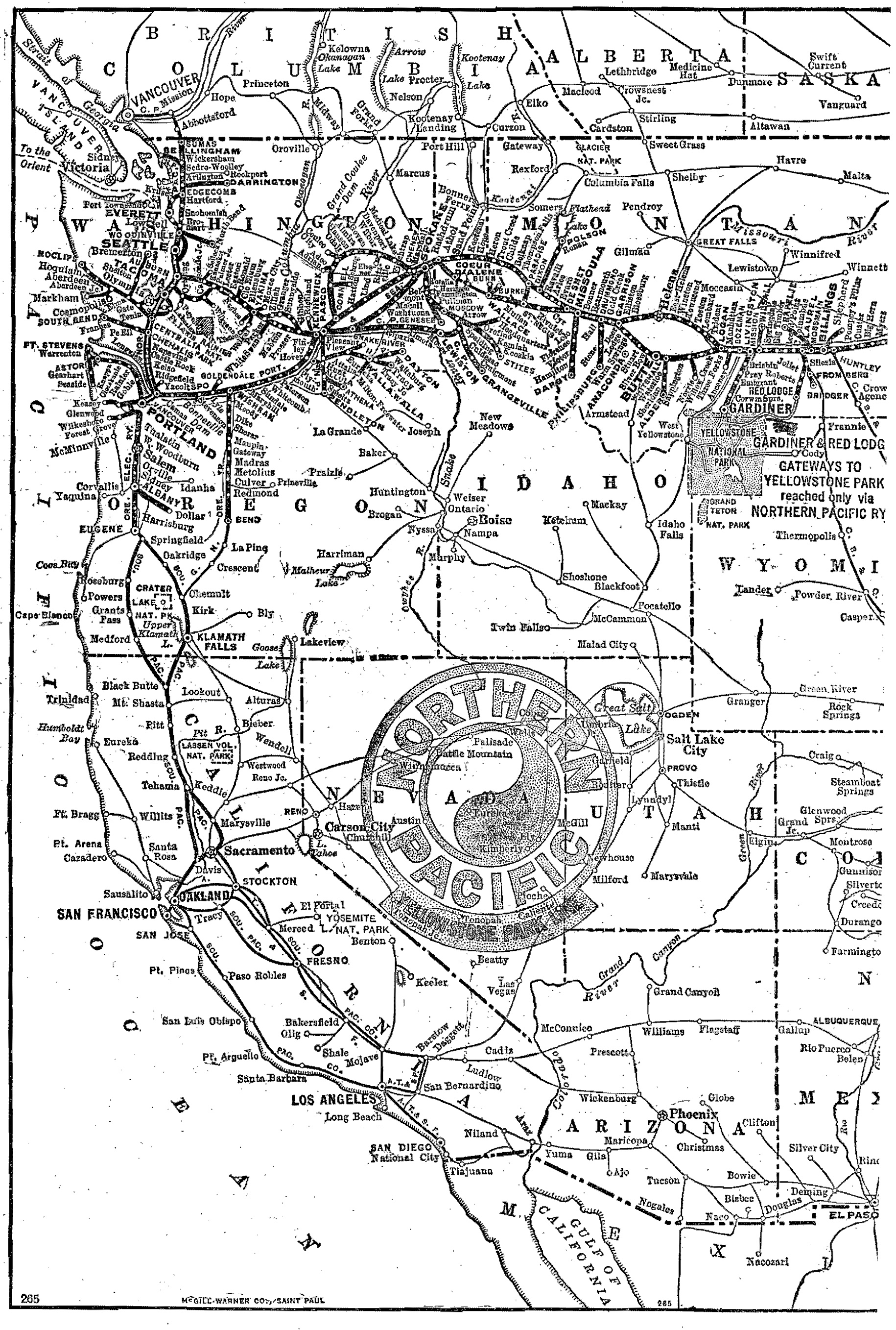

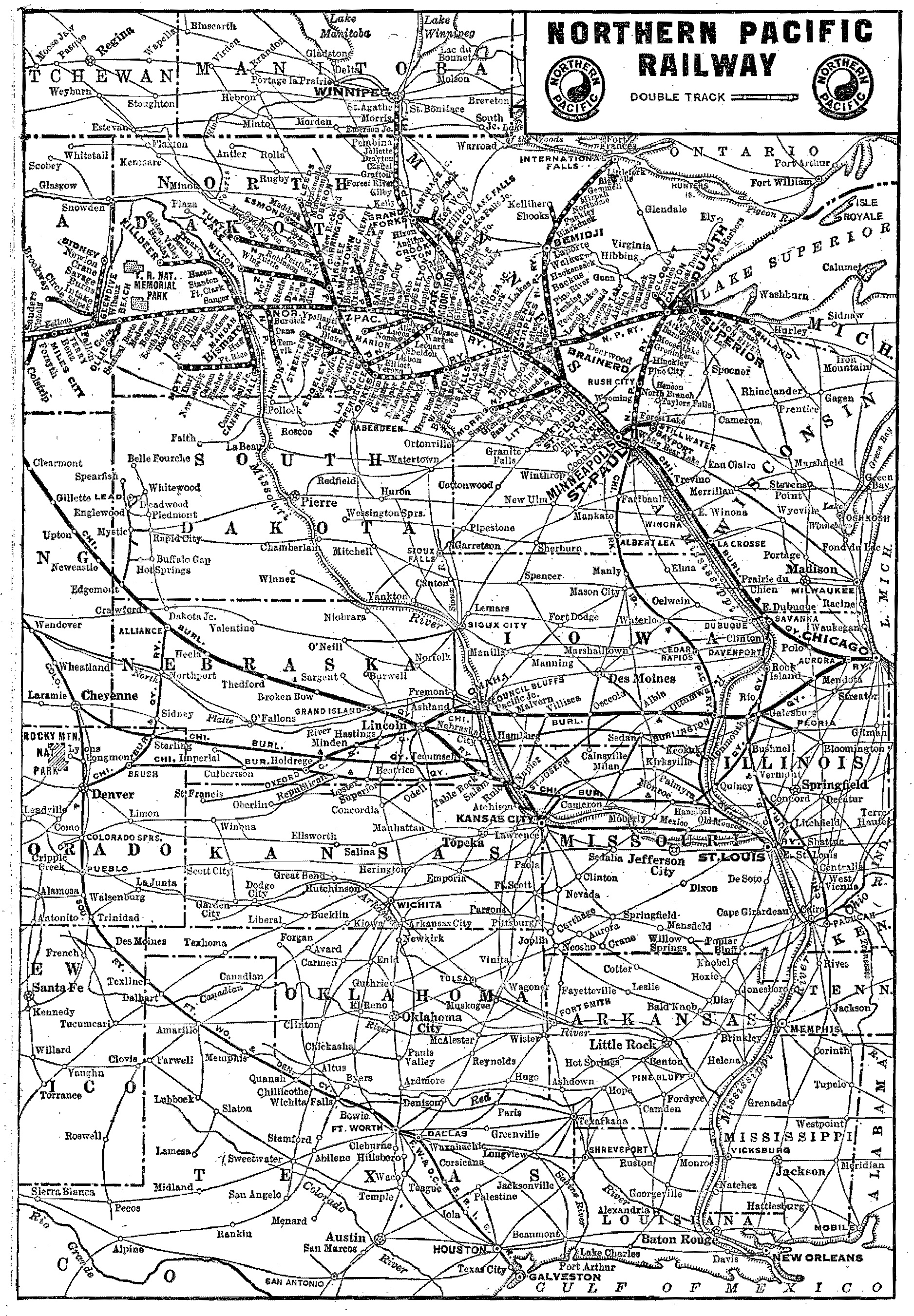

System Map (1953)

Unfortunately, despite many attempts neither Perham nor other politicians could garner enough support for government loans. These would have greatly aided the enterprise but the Transcontinental Railroad had cost so much money Washington soured on the idea of funding another such undertaking.

While the Northern Pacific was awarded land grants it would have to raise the needed capital on its own. It was further handicapped by being unable to mortgage the property. In the end, Perham's efforts went nowhere and the charter lay dormant for years. A new individual then joined the project, J. Gregory Smith.

After he also failed to achieve federal support he attempted to woo prominent Eastern/Midwestern railroaders. They also showed little interest. Smith's efforts did, however, procure two important changes; an extension of NP's completion date (July 4, 1877) and an approval to mortgage.

Jay Cooke

The latter was particularly important as it meant $100 million in construction bonds could be immediately sold. The project now had some merit which saw Jay Cooke and his banking firm, Jay Cooke & Company, enter the picture.

He had made a name for himself during the Civil War by selling war bonds throughout the United States and Europe. After coming on board his banking company, in essence, gained control of the NP. In the summer of 1869 more surveys were carried out on a planned route running west from Lake Superior.

It would pass through the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul, head through the Dakotas and Montana (then territories), and reach Spokane. From that point the corridor would head southwesterly towards the Columbia River and follow it into Portland, Oregon.

Northern Pacific FTA #5409A (ex-#6010A) is seen here at Sumas, Washington on January 3, 1965. By this date this classic locomotive had already been in service for 20 years. Warren Calloway collection.

Northern Pacific FTA #5409A (ex-#6010A) is seen here at Sumas, Washington on January 3, 1965. By this date this classic locomotive had already been in service for 20 years. Warren Calloway collection.Construction

Finally, what was dubbed the "Cascade Branch" would be built due west through Washington and penetrate the Puget Sound region. The entire project was estimated to cost more than $85 million. The railroad began construction from Thomsons Junction, slightly west of Duluth, on February 15, 1870.

Here, the NP met another Cooke-controlled subsidiary, the Lake Superior & Mississippi, which had opened to St. Paul/Duluth via a southwesterly heading. Within two years, Cooke had managed to sell an impressive $30 million and, by 1872, the NP was opened to Bismarck, Dakota Territory (450 miles). In addition, a western component was completed between Kalama and Tacoma, Washington Territory (roughly 100 miles).

1873 Bankruptcy

For a moment it seemed the entire scheme might actually be finished relatively quickly. However, bond sales soon slowed to a trickle and Gregory Smith, then NP's president, resigned in August, 1872.

As the company's fortunes failed to improve both Jay Cooke's firm and the railroad slipped into bankruptcy on September 18, 1873 setting off a chain reaction of bank failures, causing the United States to slip into a depression.

With a bleak future, along with a woefully inadequate traffic base, it appeared the railroad's fate was sealed. As officials fought off Congressional attempts to revoke NP's land grants they managed to complete a short western branch from Tacoma to Wilkeson where coal was discovered (financed entirely through the road's earnings back east). The company was subsequently reorganized in 1875 and came under the control of eastern capitalists.

As Mike Schafer notes his book, "More Classic American Railroads," these new owners paved the way for the crucial financing needed to see its completion through $40 million in new bonds.

As the economy slowly recovered so did NP's earnings power; first, a subsidiary known as the Western Railroad Company of Minnesota completed a direct link between Sauk Rapids and Brainerd, which offered a through route from those points into St. Paul.

Expansion

The next priority involved finishing the railroad before its latest Congressional extension (July 4, 1879) expired. If not, the government had authorization to cancel its charter. While the NP ultimately failed to meet this deadline, revocation of its charter proved extraordinarily difficult and was never successfully carried out.

In the meantime, work resumed on all fronts and by 1880 it appeared the project would, at long last, be finished. However, as was so often the case during that era, powerful interests worked very hard to block or stall the effort.

These parties, notably the Union Pacific, managed to preclude NP from obtaining further extensions on its deadline while Henry Villard, who owned the very successful Oregon Railway & Navigation Company (OR&N), tried to keep it out of the Pacific Northwest.

At the time, Villard's OR&N (incorporated on July 13, 1879), controlled all trade along the Columbia River through a combination of steamboats and rail service.

But, when it appeared increasingly unlikely that he could stop Northern Pacific's advance, the wealthy businessman purchased control of the railroad in 1881 through a new holding company known as the Oregon & Transcontinental Company.

Northern Pacific NW2 #104 switches the "North Coast Limited" at St. Paul Union Depot in September, 1962. Rick Burn photo.

Northern Pacific NW2 #104 switches the "North Coast Limited" at St. Paul Union Depot in September, 1962. Rick Burn photo.Completion

Villard's ownership, though, did not amend NP's outlook as it pressed on towards completion (which still required more than 900 miles of new construction). There were changes, however. The biggest involved the western approach; instead of building its own line, Villard's OR&N was utilized along the Columbia River.

As NP's progress continued westward, it breached Bozeman Pass within Montana's Belt Mountains via a 3,610-foot tunnel completed on October 28, 1882.

Less than a year later, during June of 1883, rails arrived in Helena. Things became more difficult as crews dealt with the rugged topography of western Montana and northern Idaho.

Some of the most impressive engineering feats here included O'Keefe's Canyon Trestle (1,800-feet long and 112-feet high), Marent's Gulch Trestle (860-feet long and 226-feet high), and the 3,850-foot tunnel over Mullan Pass.

Like all of the West's major transcontinental railroads, construction crews witnessed incredible hardship but those in charge persevered; workers from the east met their western counterparts in Hell Gate Canyon (near Helena) on August 23, 1883. A final spike ceremony was held in Gold Creek, Montana on September 8th where a number of high ranking dignitaries, some as far away as Europe, were on-hand to see the event.

Modern Network

It also marked another major milestone in American history as the country now enjoyed two routes to the Pacific coast. But for its many accolades, the Northern Pacific had still not fulfilled its charter by directly serving the Puget Sound. Utilizing the OR&N to reach Tacoma would not suffice.

Furthermore, this connection was not indefinitely guaranteed when Villard resigned as NP's president in 1884 (the OR&N would eventually wind up under rival Union Pacific's control by 1887).

To remedy this situation, officials began construction on the so-called, 248-mile "Cascade Branch" that year where grading commenced due west from Pasco, Washington on July 1, 1884.

It headed in a northwesterly direction away from the Columbia River and carried relatively gentle grades until it neared Ellensburg. Here, it met the formidable Cascade Mountains and required even more impressive engineering accomplishments.

The most spectacular was the tunnel over Garfield Pass, later known as Stampede Pass, which sat at an elevation of 2,852 feet. The completed bore was 1.8 miles in length and completed on May 27, 1888.

By this time work had already been finished across the remainder of the branch and the Northern Pacific finally enjoyed a direct route to the Puget Sound.

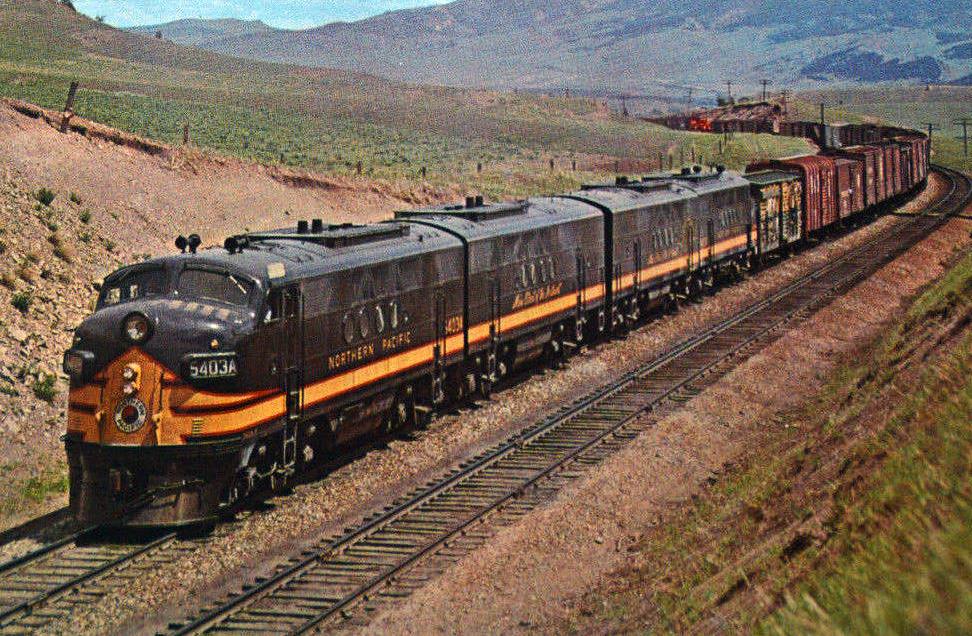

A perfect, A-B-B-A lashup of Northern Pacific FTs, led by #5403A, lead a freight extra towards Bozeman Tunnel west of Livingston, Montana, circa 1950. Note what appears to be a Chicago & North Western stock car and Baltimore & Ohio "Wagon Top" boxcar directly behind the locomotives.

A perfect, A-B-B-A lashup of Northern Pacific FTs, led by #5403A, lead a freight extra towards Bozeman Tunnel west of Livingston, Montana, circa 1950. Note what appears to be a Chicago & North Western stock car and Baltimore & Ohio "Wagon Top" boxcar directly behind the locomotives.Following the railroad's opening it added several hundred miles in secondary branches to increase freight business. In the end, Northern Pacific's independence was short-lived due, in part, to its excessive debt load brought about through its construction.

By 1890 this number had soared to over $100 million and the financial Panic of 1893 led to its second receivership on August 15th. It was reorganized on March 16, 1896 as the Northern Pacific Railway. In 1893, James J. Hill, the "Empire Builder," had completed his own railroad to the Puget Sound, the Great Northern Railway.

As his portfolio continued to expand the book, "The Great Northern Railway, A History," by authors Ralph W. Hidy, Muriel E. Hidy, Roy V. Scott, and Don L. Hofsommer notes that he acquired control of longtime rival Northern Pacific in late 1900. He then added the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy a year later for through service into Chicago.

Passenger Trains

The NP later regained a direct routing into Portland when subsidiary Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway opened between its namesake cities in 1908. At its peak, Northern Pacific's network stretched just over 6,800 miles; it contained 2,831 main line miles and 4,057 miles of secondary (branch) lines.

As with all the "Hill Lines," NP was a well-managed railroad that generally enjoyed successive years of profitability. It retired its final steam locomotive from main line service in January of 1958. Over the years its network was modernized in other ways with the addition of computers, microwave, and installation of centralized traffic control (CTC) in 1947.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S4 | 42-45 (NP Terminal), 713-724 | 1951-1954 | 16 |

| S2 | 107-118, 150-152, 711-712 | 1941-1949 | 17 |

| HH-660 | 125-127 | 1940 | 3 |

| S1 | 131 | 1945 | 1 |

| RS1 | 155-158 | 1945 | 4 |

| S6 | 750 | 1955 | 1 |

| RS3 | 850-863 | 1953-1955 | 14 |

| RS11 | 900-917 | 1958-1960 | 18 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | 108-109, 111-112, 119-124, 153-154, 160-174 | 1941-1945 | 27 |

| VO-660 | 128-130 | 1940-1942 | 3 |

| DRS-4-4-1500 | 175-176 | 1948 | 2 |

| DRS-6-6-1500 | 177 | 1948 | 1 |

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| NW | 100 (First) | 1938 | 1 |

| SW900 | 100 (Second) | 1957 | 1 |

| NW2 | 101-106 | 1940-1941 | 6 |

| SW7 | 107-114 | 1949 | 8 |

| SW9 | 115-118 | 1952-1953 | 4 |

| SW1200 | 119-177 | 1955-1957 | 59 |

| GP9 | 200-375 | 1954-1958 | 176 |

| GP18 | 376-384 | 1960 | 9 |

| GP7 | 550-569 | 1950-1953 | 20 |

| SD45 | 3600-3629 | 1966-1968 | 2 |

| FTA | 6000A-6010A, 6000D-6010D | 1944-1945 | 22 |

| FTB | 6003B-6010B, 6003C-6010C | 1944-1945 | 16 |

| F3A | 6500A-6506A, 6503C-6506C, 6011A-6017A, 6011D-6017D | 1947-1948 | 25 |

| F3B | 6500B-6506B, 6500C-6506C, 6011B-6015B, 6011C-6015C | 1947 | 24 |

| F7A | 6007A-6020A, 6007D-6020D, 6507A-6508A, 6500C-6502C, 6509A-6515A, 6507C-65013C | 1949-1951 | 47 |

| F7B | 6007B-6020B, 6007C-6020C, 6050, 6510B-6513B, 6550 | 1949-1952 | 34 |

| FP7 | 6600-6601 | 1952 | 2 |

| F9A | 6700A-6704A, 6700C-6704C, 7000A-7014A, 7000D-7014D, 7050A | 1953-1956 | 41 |

| F9B | 6700B-6701B, 7000B-7014B, 7000C-7014C | 1954-1956 | 32 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 98-99 | 1943-1946 | 2 |

| U25C | 2500-2529 | 1964-1965 | 30 |

| U28C | 2800-2811 | 1966 | 12 |

| U33C | 3300-3309 | 1969 | 10 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A Through A-5s | Northern | 4-8-4 |

| B Through B-2, C-1 Through C-33 | American | 4-4-0 |

| D Through D-9, K, K-1 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| E Through E-8, P Through P-3, R, S (Various) | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| F Through F-8, Y Through Y-5 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| F-2, F-5, G Through G-2 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| H, H-1, H-3 | Switcher | 0-4-0/t |

| H-2 | Saddle Tank | O-4-2T |

| H-4 | Saddle Tank | O-4-4T |

| H-5 | Porter | 2-4-0 |

| I-1, I-2, K-1, K-2, L Through L-10 | Switcher | O-6-0 |

| M | Decapod | 2-10-0 |

| N, N-1 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| Q Through Q-6 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| T | Prairie | 2-6-2 |

| V | Shay | 0-4-4-4-0T |

| V-2 | Heisler | 0-4-4-0T |

| W Through W-5 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| X | Twelve-Wheeler | 4-8-0 |

| Z, Z-1 | Mallet | 2-6-6-2 |

| Z-2, Z-3, Z-4 | Chesapeake | 2-8-8-2 |

| Z-6, Z-7, Z-8 | Challenger | 4-6-6-4 |

A company photo of Northern Pacific's flagship, the "North Coast Limited" (Chicago - Seattle), led by F9A #6701-C as it passes through western Montana circa 1969.

A company photo of Northern Pacific's flagship, the "North Coast Limited" (Chicago - Seattle), led by F9A #6701-C as it passes through western Montana circa 1969.Burlington Northern

There had been several attempts to merge the "Hill Lines" into a unified network dating back to the early 20th century. In 1955 informal talks were again launched between the three allying railroads about regarding this issue.

This led to a formal application filed with the Interstate Commerce Commission on February 17, 1961 which would bring together the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy into the previously-named conglomerate.

It would comprise 24,500 miles and include leasing the Spokane, Portland & Seattle for a period 10 years before its absorption into the parent company. In typical ICC fashion the process was slow and tedious.

Finally, on March 31, 1966 the agency surprisingly voted against the merger in a 6-5 decision. Undeterred the three railroads continued to push forward.

A great hurdle was cleared when they worked out an agreement with the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific whereby their only transcontinental competitor was afforded eleven new western gateways.

This strategic opportunity provided the Milwaukee Road bountiful new sources of interchange traffic, particularly in conjunction with the Southern Pacific at Portland. With this issue resolved the ICC reopened hearings on January 4, 1967.

Later that year, on November 30th, the merger was approved by an 8-2 vote. As the process the railroad's name was formally changed to Burlington Northern, Inc. (BNI) during April of 1968. After overcoming a bit more legal work and objections the four railroads finally became one at 12:01 AM on March 2, 1970.

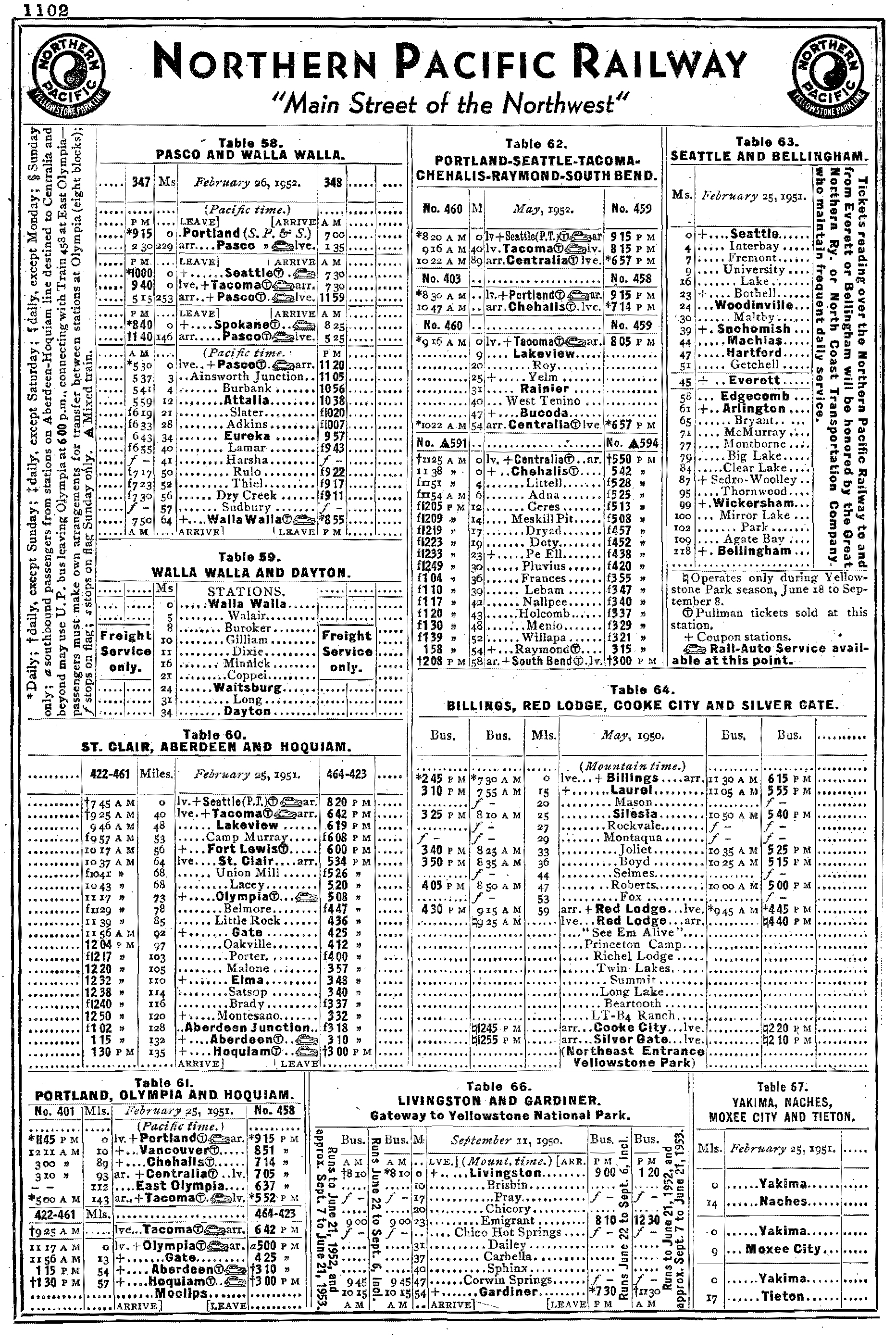

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Pennsylvania - Whiskey - Train Rides

Dec 20, 25 09:06 PM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

New Jersey Thomas The Train Rides

Dec 20, 25 06:32 PM

Here's a comprehensive guide to what you can expect at Day Out With Thomas events in New Jersey. -

Michigan Thomas The Train Rides

Dec 20, 25 06:28 PM

Here’s an in-depth look at what a typical "Day Out with Thomas" event in Michigan entails, what makes it special, and why it remains a must-visit for families.