Horseshoe Curve (Pennsylvania): A World-Renowned Landmark

Last revised: August 24, 2024

By: Adam Burns

There are many horseshoe curves throughout North America such as Milwaukee Road's Vendome Loop (abandoned), Western Maryland's Helmstetter's Curve, Santa Fe's Cajon Pass, and Canadian Pacific's Crowsnest Pass.

However, for most the term "Horseshoe Curve" describes a singular place, Pennsylvania Railroad's (PRR) legendary crossing of the Allegheny Mountains within its home state.

History

It was the company's final effort in completing its original, Harrisburg-to-Pittsburgh main line.

The project was spearheaded by PRR president John Edgar Thomson (also the railroad's first chief engineer) in an exhaustive effort to maintain the lowest possible grades through the rugged Appalachian Mountains.

His ingenious design was so remarkable it eventually earned National Historic Landmark status and became not only a popular PRR location but also a nationwide attraction. Today, it still plays hosts to thousands of visitors and remains a vital artery of successor Norfolk Southern.

Penn Central SD40 #6040 and SD45 #6204 work helper service on Horseshoe Curve on February 23, 1969. Roger Puta photo.

Penn Central SD40 #6040 and SD45 #6204 work helper service on Horseshoe Curve on February 23, 1969. Roger Puta photo.The state of Pennsylvania was rushing to improve its transportation arteries following the Erie Canal's 1825 opening, as well as various early railroads (notably the Baltimore & Ohio).

The legislature authorized construction of its own canal, known as the Pennsylvania Canal, on February 25, 1826.

Originally projected to link Harrisburg with Pittsburgh, plans were later amended for an eastern extension into Philadelphia.

With railroad fever growing, the state slightly modified the original concept by having engineers devise an interesting system of interlinking railroads and waterways, collectively known as the Main Line of Public Works (MLoPW).

While successful, by the time the 395-mile network was fully in service the iron horse was already proving itself operationally superior. From east to west the MLoPW consisted of:

- The 82-mile Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad (Originally incorporated as the Philadelphia, Lancaster & Columbia Rail Road in 1826 to link Quaker City with Columbia, it was the oldest railroad component of the modern PRR.) completed between Philadelphia and Columbia in 1834.

- The 172-mile Pennsylvania Canal linking Columbia and Hollidaysburg which opened in 1832.

- The 36-mile, incline plane Allegheny Portage Railroad from Hollidaysburg to Johnstown finished in 1834.

- The 104-mile Western Division Canal completed between Johnstown and Pittsburgh in 1830.

The B&O was a particular threat as the pioneering road served Baltimore, situated very near Philadelphia.

As cities all along the east coast fought for dominance in the Atlantic trade, Pennsylvania worried it would be eclipsed by its next door neighbor.

Pennsylvania Railroad

The legislature hurriedly formed the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1846 and work soon began on an all-rail corridor across the state. Entire libraries could be written on the "Pennsy," ranging from its corporate history and locomotive classes to non-rail business interests and economic impact.

For more than 120 years its Keystone logo was not only a symbol of Pennsylvania but also a corporate pillar in American commerce. For this reason, the PRR remains an institution to Philadelphia and Pennsylvania.

Ironically, despite bringing about its creation, the state had mixed feelings towards the newly incorporated railroad; if completed, it would almost assuredly prove its publicly-funded MLoPW redundant.

John Edgar Thomson, Chief Engineer

Nevertheless, the PRR project moved forward. Its chief engineer, John Edgar Thomson (appointed to the post on April 9, 1847), was tasked with selecting the best of three routes surveyed by George Schlatter in 1839.

Photos

Pennsylvania 2-8-2 #6894 in helper service near Horseshoe Curve. Philip Hastings photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Pennsylvania 2-8-2 #6894 in helper service near Horseshoe Curve. Philip Hastings photo. American-Rails.com collection.Following much deliberation he concluded the central corridor ideal; it was the most direct with the lowest grades.

The line would follow the Susquehanna River north to the Juanita River where it turned due west all of the way to Petersburg before veering slightly northwest and then south into Altoona via the Little Juanita River.

What was known as PRR's Eastern Division, from Harrisburg to Ducansville, was opened for service by October, 1850.

Alignment

At the latter point a connection was established with the state's Allegheny Portage Railroad. With this segment's completion the PRR began work on its Western Division.

It was built through the Allegheny Plateau and, once again, stuck largely to river valleys in an attempt to keep grades under 1.8%, as Thomson had directed.

From Pittsburgh, the line struck out northward along the Allegheny River before turning eastward at Freeport along the Kiskiminetas River.

At Saltsburg the waterway became known as the Conemaugh River and was followed all of the way to Portage, via Johnstown.

At the former point the Little Conemaugh River valley was utilized into Cresson. The final remaining obstacle was the impenetrable Allegheny Mountains, a barrier preventing easy connection of the two divisions.

An A-B-A set of Pennsylvania F7's pass beneath the signal bridge as they climb the grade just west of Kittanning Point, Pennsylvania during the 1960's. The structures seen protruding from the A units' roof-lines was Pennsy's unique "Trainphone" system, used in the days prior to modern wireless radio.

An A-B-A set of Pennsylvania F7's pass beneath the signal bridge as they climb the grade just west of Kittanning Point, Pennsylvania during the 1960's. The structures seen protruding from the A units' roof-lines was Pennsy's unique "Trainphone" system, used in the days prior to modern wireless radio.There was no way around the mountain and no natural valley through it existed.

Thomson was forced to improvise while still maintaining the maximum grade he had set forth. What was dubbed the Mountain Division was very short (under 40 miles) although it became the railroad's most famous segment.

In their book, "Pennsylvania Railroad," authors Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon note that a direct alignment from Altoona to the mountain's eastern ridge would have required a brutal 4.5% grade.

Thomson also ran into a funding problem; although work had begun in 1851 he was unable to convince the state or railroad President William C. Patterson to provide financing for the line's completion.

Construction

A fervent believer in the PRR, Thomson used his influence to reach the presidency in 1852. Now controlling the reigns he quickly raised $3 million in bonds; the route subsequently headed west from the small hamlet of Altoona (officially incorporated on February 6, 1854), situated just over 7 miles north of Ducansville.

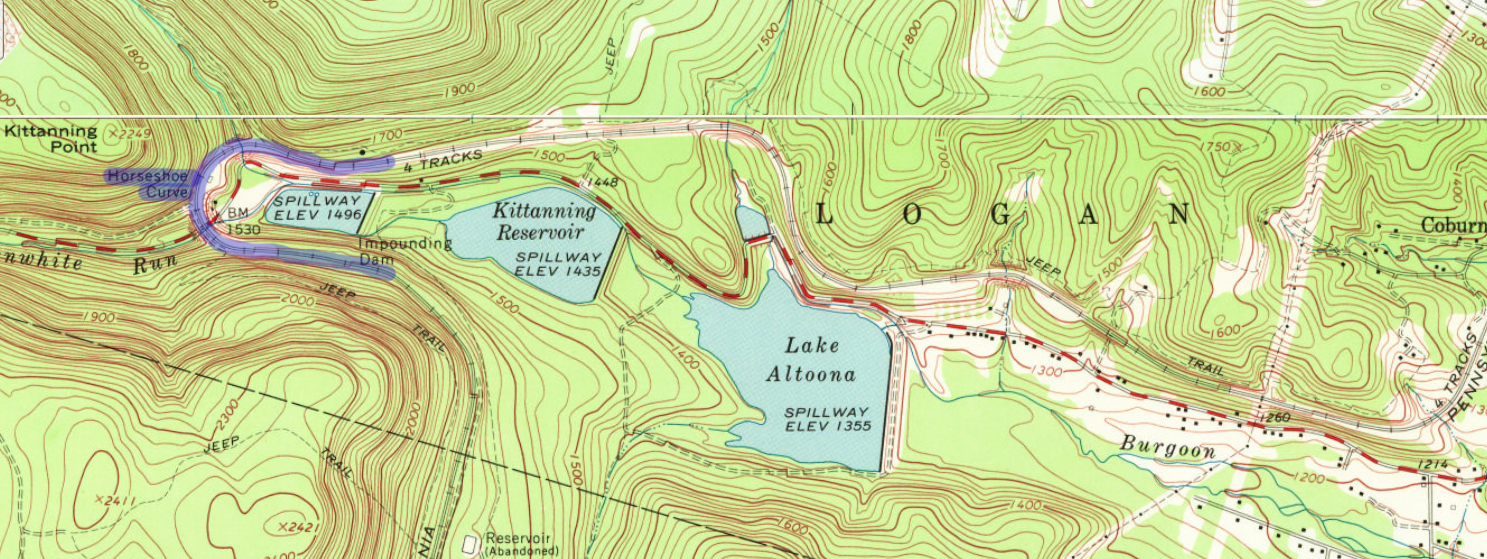

Following great deliberation Thomson and his engineers realized an alignment heading out of the valley along Burgoon Run, hugging the mountainside to a location known as Kittanning Point, and swinging around to the other side via a massive curve could maintain a grade of less than 1.8% into Cresson.

What became known as Horseshoe Curve was officially opened on February 15, 1854. In later years Burgoon Run was utilized as the city's reservoir, which still holds true today.

The article, "Horseshoe Curve: And Approach To Gallatzin Tunnels," from the May, 1952 edition of Trains Magazine, notes the grade through the curve totaled 1.45% (or 76.6 feet per mile) while the grade out of Altoona ascended 1.75% (or 92.4 feet per mile).

The curve itself is composed of two separate bends at slightly different radii. The northerly/easterly curve features a radius of 637 feet while the southerly/westerly curve holds a radius of 609 feet. Overall, the entire curve is 9 degrees.

Even into the diesel era, the PRR almost always utilized helpers for westbound freights as trains out Altoona would be 122 feet higher at the western approach (the western/southern "calk" is 1,716 feet high while the eastern/northern "calk" stands at 1,594 feet in height).

Beyond, the grade averages 1.729% to the summit at the Gallatzin Tunnels, which include PRR's original two bores as well as the Allegheny Portage Railroad's 2,000-foot New Portage Tunnel.

- The middle, originally known as the Summit Tunnel and now known as Allegheny Tunnel, is 3,612 feet in length and situated at an elevation of 2,167 feet.

It was completed by the PRR in 1854. Its northern counterpart is the newest, Gallatzin Tunnel, finished in 1904 and was also 3,612 feet in length. -

As the most southerly bore it was finished in 1855/1856, part of the state's endeavor to replace the incline plane railroad and improve its MLoPW. The route headed due west out of Ducansville via Blairs Gap Run and even included its own miniature horseshoe curve, known as Muleshoe Curve.

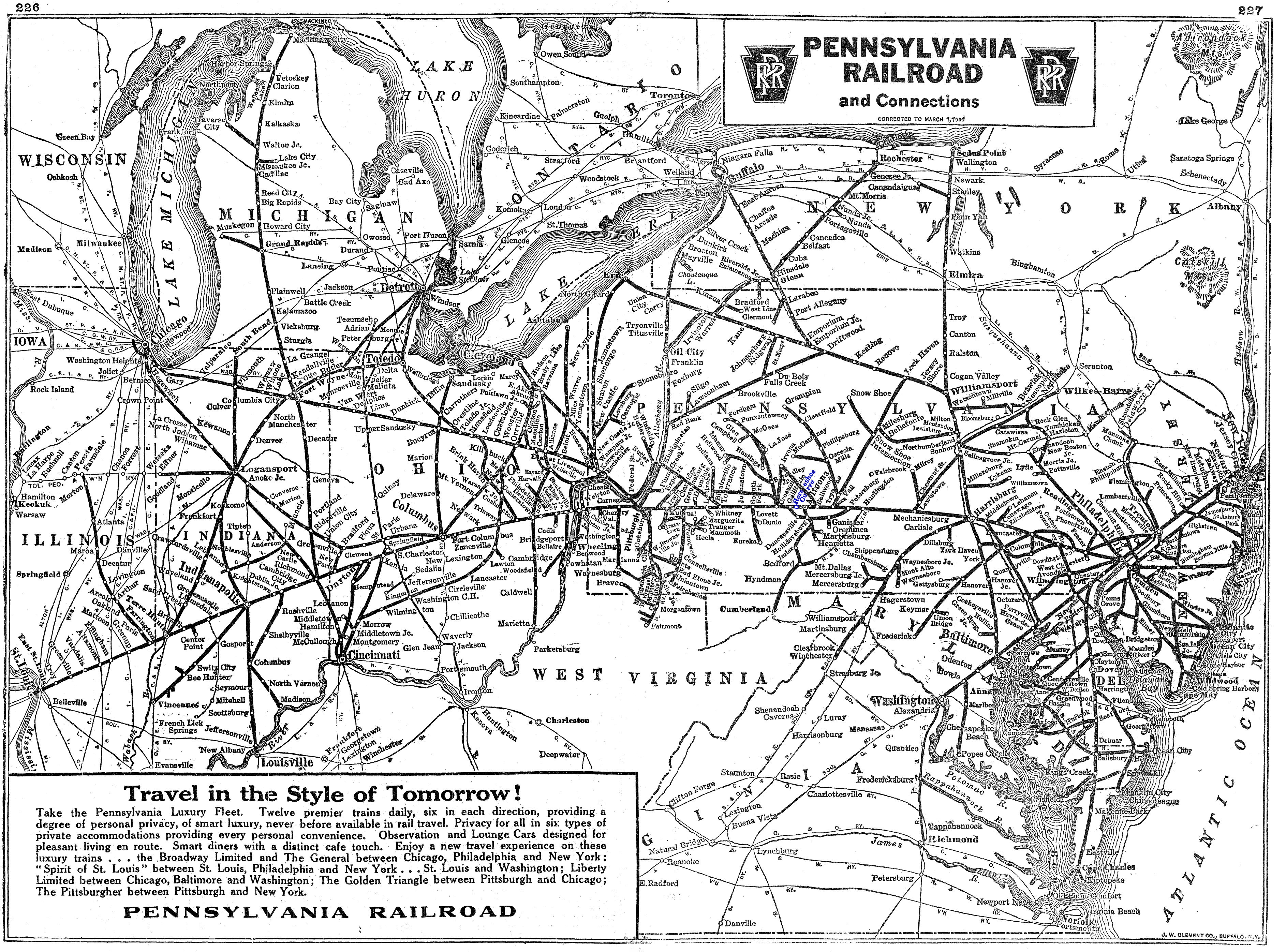

Maps

Unfortunately, the PRR's opening ruined the MLoPW. Just as the state had feared, the railroad's direct routing made its project superfluous; where once the PRR had to pay state tolls between Philadelphia and Lancaster, as well as from Duncansville to Cresson (to link its Eastern and Western Divisions) it purchased the MLoPW outright in 1857.

Operation

Much of the right-of-way was quickly abandoned although the New Portage Tunnel proved useful by handling eastbound traffic. This allowed the Allegheny [and later Gallatzin] Tunnel to move predominately westbound movements.

The PRR immediately saw a boom in freight and passenger traffic as Harrisburg-Pittsburgh travel times were reduced to only 13 hours. In the early years the location was marketed as the "Horseshoe Curve Route" and as the PRR grew it turned into a popular tourist attraction.

The Steel City blossomed into an industrial powerhouse and PRR's gateway to the west where acquisitions allowed it to eventually reach Chicago and St. Louis.

The Pennsy quickly eclipsed the B&O and in time became the most powerful eastern trunk line, even besting Cornelius Vanderbilt's future New York Central & Hudson River empire. While the route initially featured only one track it later grew to four.

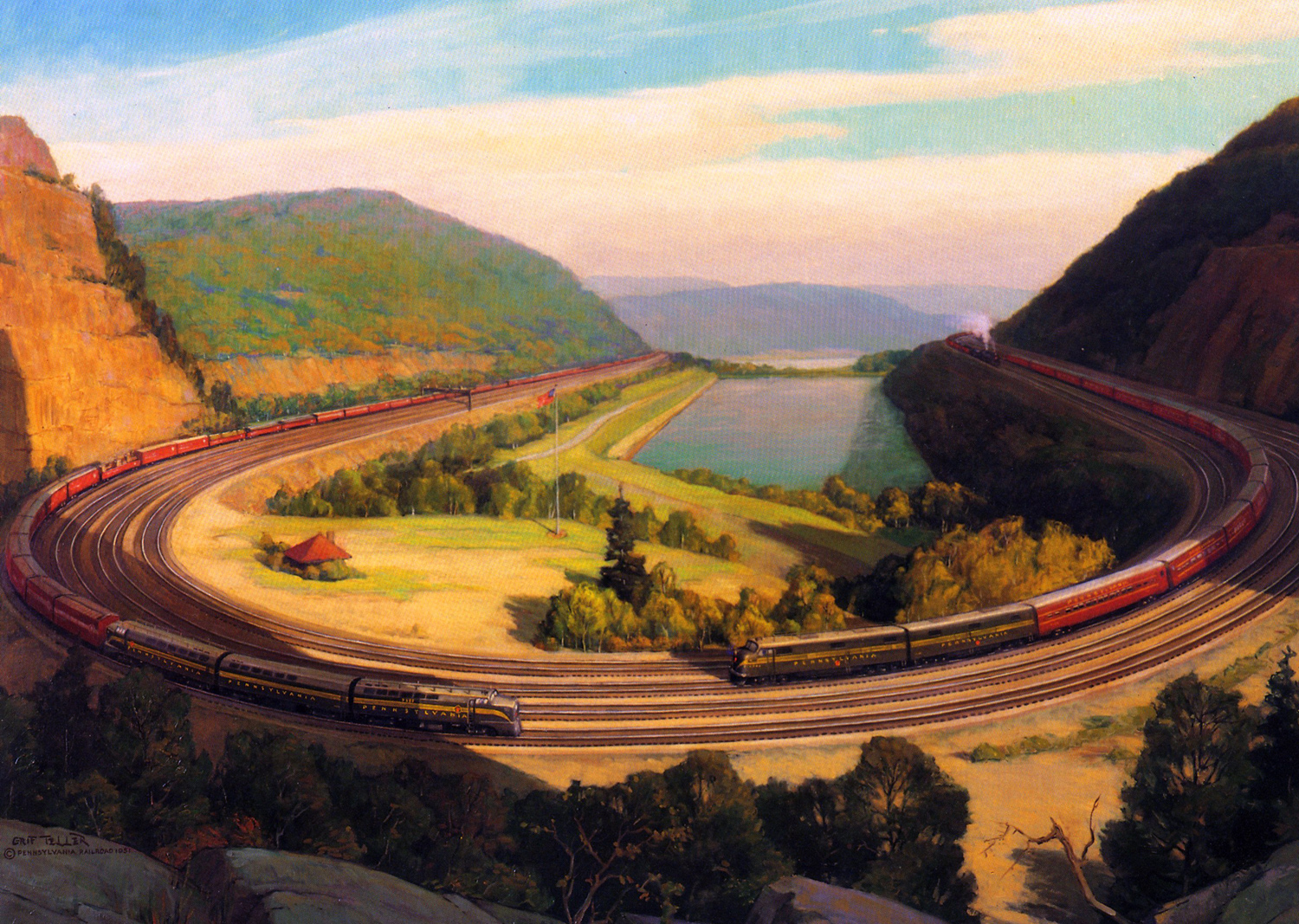

"The Horseshoe Curve." Artwork by Grif Teller, featured in the Pennsylvania Railroad's 1952 annual calendar.

"The Horseshoe Curve." Artwork by Grif Teller, featured in the Pennsylvania Railroad's 1952 annual calendar.In addition, Altoona was selected as PRR's primary locomotive and maintenance shops. Known as the Altoona Works, Harry T. Sohlberg notes in his article "Horseshoe Curve" from the March, 1941 issues of Trains Magazine its roundhouse was a complete circle with 50 engine-house pits capable of storing 385 locomotives.

There was also the Juanita Shops, Altoona Machine Shops, Altoona Car Shops, South Altoona Foundries, Test Department, and Locomotive Test Plant. Today, while somewhat scaled down it remains open under Norfolk Southern.

In addition, the nearby Railroaders Memorial Museum highlights the history of this facility, the region's rail heritage (including Horseshoe Curve), and the role railroaders have played within America.

Today, the curve includes only three tracks. Due to the decline of passenger trains, Conrail removed one track following its 1976 startup.

In any event, the location remains as busy as ever, hosting more than 50 freight trains and a few Amtrak services per day. To read more about the Pennsylvania Railroad please click here.

Since 1879 a park dedicated to the engineering marvel has been located in the bowl of the curve. In 1932 an access road was completed to the park and in 1957 the PRR dedicated a retired 4-6-2 steam locomotive (Class K4s #1361) at the park (it has since been replaced by Pennsylvania Railroad GP9 #7048).

On November 13, 1966 the curve was adorned with the rare status as a National Historic Landmark and in the late 1980s the National Park Service became involved by permanently maintaining the park's facilities and grounds.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern Railroad: Connecting the Heartland

Jan 20, 25 11:31 PM

The Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern has been in operation since 2014, acquiring the western end of the western end of the former Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern from Canadian Pacific. -

Louisville and Indiana Railroad: Maintaining The PRR In The Midwest

Jan 20, 25 04:24 PM

The Louisville & Indiana operates 106 miles of the former PRR's main line between Indianapolis and Louisville. The short line has been in operation since 1994. -

New England Central Railroad: Maintaining The CV

Jan 20, 25 04:09 PM

The New England Central has been in operation since 1995 operating most of the old Central Vermont Railway. Today, it is a Genesee & Wyoming subsidiary.