Hoboken Terminal, DL&W's Spectacular Watefront Station

Last revised: September 10, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The majestic Hoboken Terminal is the last survivor of the great Hudson River (New Jersey) waterfront stations still serving in its original function.

The facility was funded and operated by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western (DL&W), designed by Kenneth M. Murchison in the Beaux-Arts style. Today, the terminal has vastly changed from the dark days of the 1970s.

The building was first restored in the latter 1980s bringing it up to standards for general commuter service. However, its most thorough restoration began in the mid-2000s when plans were formulated to restore the structure essentially back to its original appearance.

This long process was largely finished by 2011 when the former ferry slips were returned to service.

Today, commuters and sightseers can again catch a ride across the Hudson just as they could have generations ago during the "Golden Age" of rail travel.

The Hoboken Terminal as seen from across the Hudson River on the evening of September 9, 2009. Photo by Wikipedia user "Muncharelli."

The Hoboken Terminal as seen from across the Hudson River on the evening of September 9, 2009. Photo by Wikipedia user "Muncharelli."History

For most railroads attempting to serve the country's most important port city the New Jersey waterfront would be as close as they would get.

The two exceptions here were the East's most powerful systems, the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central.

The former reached Manhattan thanks to the efforts of its president, Alexander Cassatt, who spent millions during the early 20th century to lay tunnels beneath the Hudson while the latter was born on the island.

For all other railroads the only way to provide service was via a waterfront terminal and ferries. The most notable facilities were operated by:

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western

- Central Railroad of New Jersey (whose ornate Jersey City Terminal is the only other such facility still standing),

- Erie Railroad

- Pennsylvania (before it built into Manhattan)

There were other railroads which shared these facilities including the Baltimore & Ohio, Lehigh Valley, and Reading.

While the Lackawanna was never provided significant intercity services it did field a small fleet of trains such as the Phoebe Snow, Owl, New Yorker, and Pocono Express serving Buffalo.

Hoboken Terminal's front façade and aged copper gives the building a timeless appearance. Wally Gobetz photo.

Hoboken Terminal's front façade and aged copper gives the building a timeless appearance. Wally Gobetz photo.The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western was formed in 1851 and was one of the Northeast's earliest railroads.

It has ties tracing back to the Liggetts Gap Railroad of 1832 (chartered to build a 56-mile route from Scranton to Great Bend, Pennsylvania) and the Hoboken Ferry Company of the 1770s (according to Mike Schafer's book, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III," this company was once led by a Revolutionary War commander, Colonel John Stevens).

During its peak years the DL&W operated a 396-mile main line connecting Hoboken with Buffalo with additional services to Oswego, Northumberland, Syracuse, and Ithaca.

Anthracite coal paid the bills and was always the company's most important business.

In addition, the Lackawanna operated a robust commuter business throughout the New York metropolitan region, even going so far as to electrify many of these local routes between 1930-1931 in an effort to increase speeds and improve operations.

Its coal traffic largely tailed away after World War II but the railroad weathered the loss better than most others thanks to an excellent management team.

The company was so well run it had never experienced a major bankruptcy or reorganization in its corporate history. Alas, as traffic sagged throughout the 1950s the DL&W needed a merger partner resulting in the union with the Erie to form Erie Lackawanna in 1960.

The construction of Hoboken Terminal was the result of a spectacular blaze during 1905 which had destroyed the original structure due to a ferry catching fire while docked.

As Solomon notes in his book, "Railroad Stations," the Hopatcong caught fire just before Midnight on August 7th and quickly spread throughout the facility.

Fortunately, the DL&W was experiencing record profits and had the resources to erect another grand terminal, which it wasted no time in doing.

The new facility was also the vision of President William Haynes Truesdale who had been working to modernize the railroad since he became president in 1899.

Perhaps his most noted accomplishment was the construction of the Lackawanna/New Jersey Cutoff, an arrow-straight upgrade to its main line stretching 25-miles between Port Morris, New Jersey and Slateford, Pennsylvania. It eliminate numerous grades, curves, and low clearances opening for service in 1915.

To show off the railroad's growing prestige it planned an elaborate new facility hiring noted architect Kenneth M. Murchison for the project.

Murchison, a native of New York City, had worked on other projects for the Lackawanna and also designed stations for the Pennsylvania, Florida East Coast, and Lehigh Valley.

He had studied in Paris and became known for designing buildings in the Beaux Arts style, which would include Hoboken. Since it was a waterfront terminal it did not carry the traditional look of a railroad station although this certainly did not take away from its beauty.

The approach tracks entered slightly south of the main, 750-foot long head house, meaning the staging tracks and platforms were not aligned with it. This resulted in the main terminal being slightly angled to the northeast in alignment with the river.

Perhaps the building's most recognizable feature was its copper-adorned façade. According to Brian Solomon's book, "Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals," it is believed this copper was the very same material left over from the construction of the Statue of Liberty.

Interestingly, its use was purely by happenstance. At the time of the terminal's construction there was so much left over it needed to either be used or sold for scrap. As a result, Murchison gladly incorporated it into the design.

The building's other remarkable feature was a new train shed, later replicated in other stations. The work of DL&W's chief engineer, Lincoln Bush, the structure was replicated by other railroads and carried his name.

Typical train sheds of the day were arched or rounded whereas Bush created a cantilevered design of steel, glass, and concrete that offered lower construction and maintenance costs.

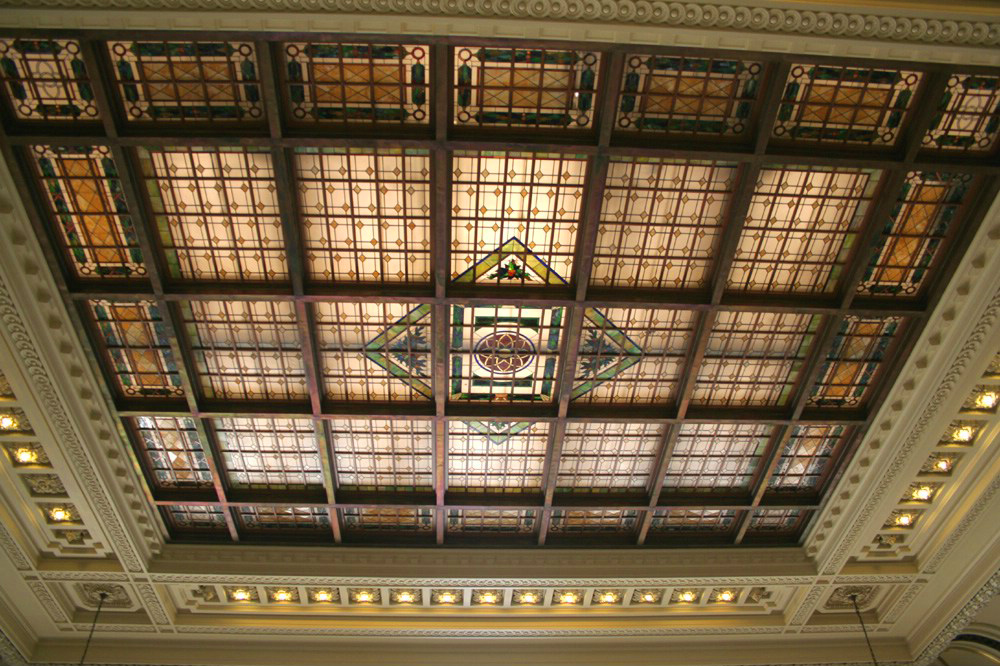

Inside, Hoboken featured a Tiffany glass ceiling rising more than fifty feet above the main waiting room with walls of limestone, iron, and bronze.

Additionally, the main concourse was adorned in Greek Revival motifs. The building would also have a gorgeous double staircase from the main waiting room featuring ornate cast iron railings, which carried passengers above to waiting ferries.

While the terminal hosted Lackawanna's best known long-distance trains, such as the Phoebe Snow and New Yorker, locals depended upon it for its commuter services throughout the Tri-State area.

Another view of Hoboken Terminal and its ferry slips which are once again operational. Joe Mabel photo.

Another view of Hoboken Terminal and its ferry slips which are once again operational. Joe Mabel photo.Hoboken's first blow came during World War II when, as Schafer points out, its clock tower was removed in 1942 to reclaim its copper for the war effort.

Its second occurred after the war as folks abandoned trains for cars and planes. By the time Amtrak began service in the spring of 1971 all through, intercity trains stopped calling to the building (after their merger Erie and DL&W had consolidated most services at Hoboken).

According to Roger Grant's authoritative title, "Erie-Lackawanna: Death Of American Railroad, 1938-1992," the final westbound Lake Cities, train #5, departed the terminal on the evening of January 5, 1970.

It arrived at Chicago's Dearborn Station the following afternoon and signaled the end of 87 years of continuous service between New York and Chicago.

Thankfully, the terminal has always functioned as a commuter station even during the industry's lowly years of the 1970s and 1980s which helped save from potential demolition.

Another saving grace was likely the loss of Manhattan's nearby Pennsylvania Station, razed during the 1960s in a last ditch effort by the PRR to stave off bankruptcy.

The loss of this architectural masterpiece also saved nearby Grand Central Terminal following an angry uprising preventing Penn Central from also leveling that building.

After its first restoration in the 1980s, Hoboken Terminal received a more thorough update beginning in the 2000s with the restoration of its iconic clock tower, unveiled to the public in 2007.

According to Stephanie Hoagland, an architectural historian on the tower project:

"We did not have any original drawings to use for the reconstruction. We had to completely re-design the tower based upon historic photographs and post cards.

I walked around the terminal many times trying to find elements remaining on the building which would have been similar to those used on the original tower. It took months of research and hard work.

We went through multiple designs tweaking and adjusting the size and design of the various elements to ensure that the final design was to scale and visually compatible with the original tower.

We also worked with the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office to get their approval for our final design. A lot of hard work went into the reconstruction [involving designers, fabricators, and contractors]."

The tower is entirely authentic with a clock, keeping time, at the top and adorned in matching copper. To read more about the terminal please click here.

Additionally, the original neon-lit "Lackawanna" sign also has been added to the tower. It's quite a sight to see during the nighttime hours.

The last restoration project of the building was its ferry slips, completed in 2011 and again serve in their original capacity as they did decades ago.

While long distance trains may never again call at the station it has held a much better fate than many other grand railroad stations and terminals across the country, and besides still serving in much of its original function you can visit the building any time you wish to see the magnificent architecture of the waiting room, concourse, and even the train shed of Hoboken Terminal.