Lackawanna Railroad: Map, History, Viaducts, Rosters

Last revised: October 11, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (better known as the Lackawanna and not to be confused with current short line, Delaware-Lackawanna) was another of the Northeast's many anthracite carriers with a history tracing back to the early 19th century.

During the company's height it never reached 1,000 miles in size but was nevertheless a well-managed company throughout its corporate history.

As a result, it avoided bankruptcy from the time of its formation (early 1850s) until its merger with the Erie more than a century later.

It has been argued that had Lackawanna's top officers been allowed to oversee the new Erie Lackawanna (1960), it would have been a much more successful operation.

The DL&W completed two notable "Air Line" improvement projects during the early 1900s which greatly improved operations; these included the New Jersey Cutoff (Port Morris, New Jersey - Slateford, Pennsylvania) and Nicholson-Hallstead Cutoff.

Magnificent feats of engineering the corridors were home to huge earthen fills and stunning viaducts made from reinforced concrete, which still stand today.

Photos

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western FT's are on point of a westbound freight stopped at Pocono Summit, Pennsylvania just after cresting the eastern slope of the Pocono Mountains on May 10, 1959. Ken Von Stueben photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western FT's are on point of a westbound freight stopped at Pocono Summit, Pennsylvania just after cresting the eastern slope of the Pocono Mountains on May 10, 1959. Ken Von Stueben photo. American-Rails.com collection.History

It seems that most of the classic railroads of New England and the Northeast can trace their heritage back to an entity predating the industry. Such was the case for the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western whose earliest predecessor was the Hoboken Ferry Company.

According to Mike Schafer's, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III," this system began during colonial times in the 1770s and was once led by Colonel John C. Stevens of Revolutionary War fame.

Stevens is also credited with receiving the first charter for a railroad in the United States, the New Jersey Railroad of 1815.

Following the creation of the DL&W, the railroad acquired the company as part of its Hoboken Terminal complex to provide ferry service across the Hudson River into downtown Manhattan.

The Lackawanna's two earliest railroad predecessors were the Liggetts Gap Railroad, incorporated on April 7, 1832 and the Delaware & Cobbs Gap Railroad, chartered on December 4, 1850.

At A Glance

Hoboken, New Jersey - Newark - Buffalo, New York Hoboken - Paterson - Denville, New Jersey Hopatcong Junction, New Jersey - Slateford Junction, Pennsylvania (Lackawanna Cutoff) Scranton - Sunbury, Pennsylvania Binghamton - Utica, New York Chenango Forks - Oswego, New York Owego - Ithaca, New York | |

Freight Cars: 11,719 Passenger Cars: 610 | |

The LGRR was envisioned to connect Slocum's Hollow (later renamed Scranton) to Great Bend, Pennsylvania, a distance of 56 miles. However, many years passed before any construction actually took place.

On April 14, 1851, the company changed its name as the Lackawanna & Western Railroad and later that year, on October 20, 1851, service was opened between both towns.

The future DL&W recognized the completion of this line as its earliest corporate heritage. The Lackawanna gained its official name on March 11, 1853 when the L&W merged with the Delaware & Cobbs Gap forming the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad.

The D&CG constructed a line from Scranton, east to the Delaware River near what is today Delaware Water Gap.

The DL&W at this time ran diagonally across Pennsylvania and enjoyed lucrative sources of freight from iron ore deposits and anthracite coal located within the Lackawanna Valley.

The railroad handled a great deal of the former for George Scranton's foundry at Oxford, New Jersey, who also promoted the DL&W (in addition, he, along with his brother Selden, helped found the city of Scranton), while the latter was a vital source of heating fuel until the early 20th century.

Logo

It was not long before the Lackawanna's leadership eyed a port connection across New Jersey. It sponsored the Warren Railroad, chartered on February 12, 1851, to run from Delaware, New Jersey to a connection with the Central Railroad of New Jersey at Hampton.

It entered service on May 28, 1856 and was formally lease by the DL&W in 1857, providing the railroad access to the Hudson River waterfront thanks to trackage rights over the CNJ.

The DL&W of this era was built to a wide, six-foot broad gauge and the Jersey Central, operating standard-gauge, accommodated its business partner by laying a third-rail along its main line (the DL&W would later relay its network to standard-gauge in a single day, on March 15, 1876).

In the meantime, the Morris & Essex Railroad (incorporated on January 29, 1835 and opened its first segment between Newark and Orange, New Jersey on November 19, 1836) was becoming a vexing situation for the Lackawanna.

The M&E was continuing to expand, reaching Dover by 1848 and Phillipsburg by 1860. The DL&W interests witnessed its growth as a serious problem to their railroad's future interests.

On December 10, 1868 the Lackawanna leased the M&E, which connected with the Warren Railroad at Washington. It now had could handle trains over its own rails across New Jersey thus discontinuing its association with the Jersey Central.

Later, the M&E formed the Newark & Hoboken Railroad, completed in 1877, which offered direct service to the Hudson River waterfront. Here, the Lackawanna would construct its beautiful Hoboken Terminal, which still stands today as an active commuter facility.

With the DL&W's eastern network largely complete it now looked to the west and an extension to Buffalo; reaching this port town along the eastern tip of Lake Erie would mean the railroad no longer needed to rely on its rival, the Erie Railroad, to ferry its freight westward.

Its first extension beyond northeastern Pennsylvania occurred while completing its eastern segments; in 1869 the Syracuse, Binghamton & New York Railroad was purchased running between Binghamton and Syracuse. It also leased the Oswego & Syracuse Railroad that same year.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western F3A #661, a GP7, and several other other F units are northbound (railroad westbound) on the Lehigh Valley at Allentown, Pennsylvania during the 1950s. The train is crossing Little Lehigh Creek. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western F3A #661, a GP7, and several other other F units are northbound (railroad westbound) on the Lehigh Valley at Allentown, Pennsylvania during the 1950s. The train is crossing Little Lehigh Creek. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.The DL&W now had a direct link to the lakes although its expansion did not stop there; in 1870 it picked up the Utica, Chenango & Susquehanna Valley Railway running north of Binghamton to Richfield Springs (via Richfield Junction) and Utica where another connection was established with the New York Central.

Finally, the Greene Railroad (also opened in 1870) linked the DL&W with the UC&SV between Chenango Forks and Greene. The Lackawanna's last major extension, a direct link to Buffalo, was thanks to Jay Gould's influence.

This noted tycoon had recently lost control of the Erie Railroad and eyed the DL&W as another means of finally connecting Chicago with New York to interchange with another road he then controlled, the Wabash, which reached Buffalo.

A subsidiary known as the New York, Lackawanna & Western was chartered on August 26, 1880 to do just that, linking Binghamton with the state's largest western city. Gould would ultimately lose his influence of the DL&W but the 207-mile extension he progressed was completed on September 17, 1882.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western E8A's are seen here at historic Hoboken Terminal during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western E8A's are seen here at historic Hoboken Terminal during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.The railroad's final notable extension was its route to Northerumberland via Scranton. This line began as the Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad, incorporated in 1852 and completed in 1856. It was acquired by the DL&W in 1873 (Sunbury was accessed through trackage rights over the Pennsylvania Railroad).

The "Road Of Anthracite's" entire network only stretched roughly 950 miles but the Lackawanna was a finely tuned operation with a diverse traffic base and highly skilled railroaders, from top to bottom, that kept it humming along.

From its earliest days, management instilled a philosophy of frugality that served it well through rough times or during an economic downturn.

It weathered the financial panics of 1873 and 1893 and even the Great Depression of 1929. However, its closest brush with bankruptcy did occur during the 1930s, under the leadership of John Davis.

Before the depression the Lackawanna was a gold-plated institution, a smaller version of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

It was so successful that it sometimes paid 100% dividends to investors! Such perks were discontinued during the depression although the road returned to profitability during World War II.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western's light road-switchers, and general switchers, wore very simple liveries as seen here on RS3 #1043 during the 1960s. By this date, the locomotive was wearing its Erie Lackawanna number; the unit was built as DL&W #905 in 1951. American-Rails.com collection.

Delaware, Lackawanna & Western's light road-switchers, and general switchers, wore very simple liveries as seen here on RS3 #1043 during the 1960s. By this date, the locomotive was wearing its Erie Lackawanna number; the unit was built as DL&W #905 in 1951. American-Rails.com collection.The company's success during the early 20th century was thanks largely to anthracite coal, it moved millions of tons of the product and before the passage of the Hepburn Act of 1906 even owned several mines. Its rich coffers provided the needed capital for a number of impressive improvement projects at this time.

The DL&W's original route through eastern Pennsylvania and western New Jersey was riddled with sharp curves and stiff grades. It embarked on rerouting improvements to alleviate these issues. The first was the widely-publicized New Jersey Cutoff, also known as the Lackawanna Cutoff.

This "Air Line" project was launched in 1908 and completed in 1911 at a cost of more than $11 million. However, it eliminated numerous curves, grades, and clearance impediments while reducing the distance between Port Morris, New Jersey and Slateford, Pennsylvania by 11 miles.

The railroad used many tons of reinforced concrete to build everything from bridges to stations, since this product was readily available along its network.

Lackawanna MU's ,working suburban service, are stopped at the beautiful station in Dover, New Jersey during the 1950s. This facility, originally built in 1848, was rebuilt by architect Frank J. Nies into its present configuration in 1901. It remains in use by NJ Transit today. American-Rails.com collection.

Lackawanna MU's ,working suburban service, are stopped at the beautiful station in Dover, New Jersey during the 1950s. This facility, originally built in 1848, was rebuilt by architect Frank J. Nies into its present configuration in 1901. It remains in use by NJ Transit today. American-Rails.com collection.A similar project was carried out in Pennsylvania, north of Scranton; known as the Summit-Hallstead Cutoff, or Nicholson Cutoff, featuring similar improvements between Clarks Summit and Hallstead, Pennsylvania.

Although both air lines featured several viaducts including Martins Creek Viaduct and Paulins Kill Viaduct (Paulins Kill is located along the now-defunct New Jersey Cutoff), Tunkhannock dwarfs them all (named for the small creek which runs below it).

Topping out at 240 feet above the valley floor and roughly a half-mile long at 2,375 feet the structure is a striking sight (made all the more impressive by Lackawanna R.R. located across the center arch).

The Lackawanna Cutoff was abandoned under Conrail in 1983 although the Nicholson Cutoff remains in use today. Interestingly, in an ironic twist, the state of Pennsylvania and New Jersey are working to restore the former for commuter service.

Infrastructure Improvements

At the turn of the 20th century, a rich Delaware, Lackawanna & Western embarked upon two primary improvement projects, the most famous of which was the Lackawanna Cutoff; carried out during the tenure of William Haynes Truesdale, the project commenced on August 1, 1908.

When it opened on December 24, 1911 the new line had cost a staggering $11 million, a total that today would equal nearly $1 billion.

The route was 28.5 miles in length and bypassed much of the old Warren Railroad between Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey and Slateford Junction, Pennsylvania.

It featured just one bore, 1,040-foot Roseville Tunnel and was largely an "Air Line" flying high above the valley below with huge fills and cuts such as the 16,500-foot Pequest Fill and 4,700-foot Armstrong Cut.

Its notable bridge was the 1,100-foot Paulins Kill Viaduct, constructed of reinforced concrete. The nearly arrow-straight route was double-tracked and proved an excellent corridor for more than 70 years.

The other noteworthy project was Nicholson Cutoff; albeit lesser-known it featured the grandest bridge, 2,375-foot Tunkhannock Viaduct, which spanned Tunkhannock Creek (rising 240 feet above the floor it is still regarded as one of the tallest concrete structures in the world), in Nicholson, Pennsylvania.

Just like the Lackawanna Cutoff the new corridor eliminated many grades and curves; it was just over 39 miles in length running between Clarks Summit and Hallstead, Pennsylvania between the important cities of Scranton and Binghamton.

The railroad began work on the line (also double-tracked) in May of 1912 and it officially opened for service on November 6, 1915. After Conrail the corridor went through various owners and today is under the direction of Norfolk Southern.

Despite the shortcomings of the Davis administration his tenure did see the electrification of commuter lines in eastern New Jersey and the company managed to weather the 1930s without falling into receivership.

In 1941, William White guided the Lackawanna through the hectic World War II years and the company was well positioned afterwards. White had also launched a new streamliner which became the company's most famous train, the Phoebe Snow, and also implemented a new high-speed time freight in 1946 named the Pioneer.

Lackawanna MU's are outbound from Hoboken Terminal at Croxton, New Jersey, circa 1958. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Lackawanna MU's are outbound from Hoboken Terminal at Croxton, New Jersey, circa 1958. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.White improved the company's financial outlook in other ways, such as acquiring formerly leased lines (resulting in savings of more than $1 million annually), modernized the property as much as possible, and acquired stock in the successful Nickel Plate Road all in an effort to curb the losses sustained from anthracite coal declines (its NKP holdings were later sold during the 1950s to stave off battle growing deficits).

System Map

He was succeeded by Perry Shoemaker in 1952 who guided the company through its final years before the merger with Erie. The Lackawanna's last president completed its transition from steam power to the much more efficient diesel locomotive, sticking largely with Electro-Motive products.

The 1950s proved a trying time for the DL&W as even its excellent leadership struggled to deal with the growing loss of its once lucrative anthracite traffic while new highways and trucks continued to erode its general freight base. In 1954 it launched piggyback, intermodal service in conjunction with the Nickel Plate as another way to offset coal losses.

According to H. Roger Grant's authoritative title, "Erie Lackawanna: Death Of An American Railroad, 1938-1992," the Lackawanna had enjoyed gross revenues of $81.7 million in 1929 just before the depression. These numbers were cut in half during the 1930s although had rebounded during the war.

Phoebe Snow

Since the Lackawanna was not a large railroad it likewise did not have an expansive passenger fleet. Its premier train between Buffalo and Hoboken was the Phoebe Snow, which replaced the railroad’s former flagship, the Lackawanna Limited.

Phoebe carried a long history with the railroad, born as a fictional character created by Earnest Elmo Calkins at the turn of the 20th century to promote its use of clean-burning anthracite coal.

Most trains of that era utilized soft, bituminous coal which produced liberal volumes of soot and ash, often times attaching itself to passenger's clothing or belongings. The artistic-rendition of a woman in snow white clothing, clean and tidy, was a big hit with the public that included the poem:

"Says Phoebe Snow

About To Go

Upon A Trip To Buffalo

'My Gown Stays White

From Morn Till Night

Upon The Road Of Anthracite'"

Under, William White, Phoebe Snow returned when the road spent $3 million on a new streamliner bearing the character's name. It began service along the 396-mile main line on November 15, 1949.

The train was a marketing sensation and the railroad even hired a model to promote it. She became one of the most popular celebrities in New York City at the time as throngs of folks from large towns and small gathered to see the new streamliner when it debuted all along the Lackawanna's system.

To ensure its future, a merger seemed inevitable. Mr. Grant notes that in 1952 the DL&W earned $10.3 million from anthracite coal but this number had declined to barely $5 million by 1957.

It was also incurring heavy losses on commuter services, a situation that plagued all the railroads serving the New York City region.

In 1954 informal talks began with the Erie and two years later the roads launched efforts for joint operations in some areas as a way to reduce red ink; on October 13, 1956 the Erie began using Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal for commuter services, ending all operations at its Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City on December 12, 1958.

In addition, the two began sharing trackage between Binghamton and Gibson, New York, via the Erie's main line, in 1957. On September 10, 1956 studies were launched regarding a merger between the Erie, DL&W, and Delaware & Hudson.

On April 13, 1959 the D&H dropped out of these discussions but the other two roads carried on with merger proceedings. During the next year the process worked its way forward until the Interstate Commerce Commission formally approved the union on September 13, 1960.

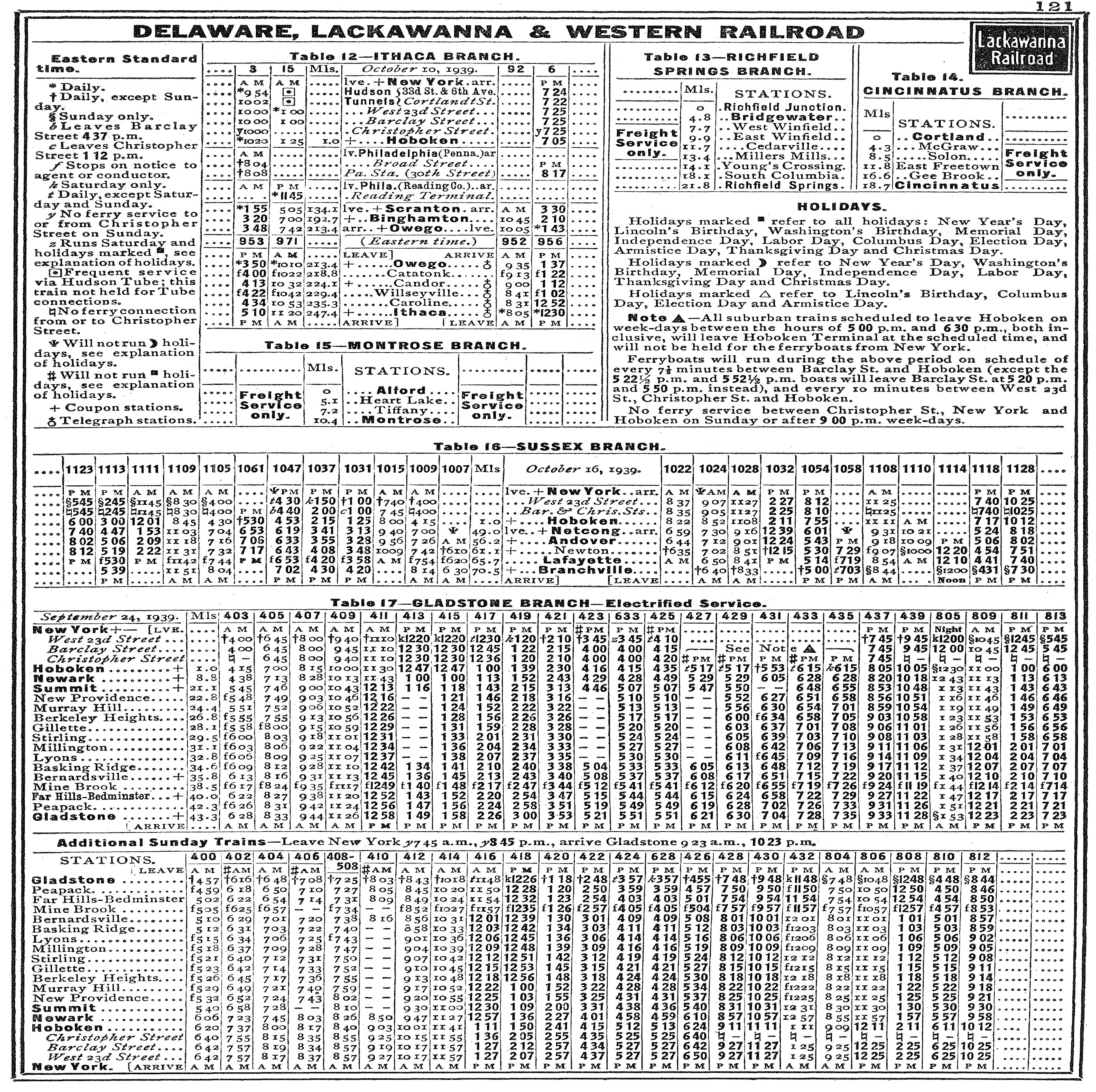

Timetables

Erie Lackawanna

The new Erie-Lackawanna Railroad (EL) officially began operations on October 17, 1960 with an entire network of 3,031 miles operating between Jersey City/Hoboken and Chicago via Buffalo.

The merger proved somewhat successful during its early days but the EL struggled as the 1960s wore on; unfortunately, the Lackawanna's management was largely ignored in favor of the Erie's.

While the latter road reached Chicago via a double-tracked route it had constantly dealt with financial difficulties (its final bankruptcy occurred in 1938), heavy debt, and questionable management at various times throughout its history.

Passenger Trains

Interstate Express: (Syracuse - Philadelphia)

Owl: (Hoboken - Buffalo)

Phoebe Snow: (Hoboken - Buffalo)

New Yorker: (Chicago - Hoboken)

New York Mail: (Buffalo - Hoboken)

Pocono Express: (Hoboken - Buffalo)

Twilight: (Hoboken - Buffalo)

Westerner: (Hoboken - Chicago)

If the Lackawanna's highly respected officers had played a more direct role in EL's operations the railroad may have survived the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Its situation was made worse by the Penn Central monstrosity formed in 1968, which ultimately collapsed two years later.

By the 1950s, however, even the once-vaunted Lackawanna was dealing with debt problems of its own. At the time of the EL merger it carried fifteen outstanding bonds while the Erie had seven.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH600 | 401-408 | 1933-1934 | 8 |

| HH660 | 409-411 | 1940 | 3 |

| S2 | 475-491 | 1945-1949 | 17 |

| RS3 | 901-918 | 1950-1952 | 18 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW1 | 427-437 | 1940 | 11 |

| NW2 | 461-465 | 1945 | 5 |

| SW8 | 501-511 | 1951-1953 | 11 |

| SW9 | 551-560 | 1951-1953 | 10 |

| SW1200 | 561-568 | 1957 | 8 |

| FTA | 601A-604A, 601C-604C, 651A-654A | 1945 | 12 |

| FTB | 601B-604B, 651B-654B | 1945 | 8 |

| F3A | 605A-606A, 605C-606C, 621A-621C, 655A-662A, 801A-805A, 801C-805C | 1946-1947 | 22 |

| F3B | 605B-606B, 621B, 655B-662B, 801B-805B | 1946-1947 | 15 |

| F7A | 611A-611C, 631A-636A, 631C | 1949 | 9 |

| F7B | 611B, 632B-636B | 1949 | 6 |

| E8A | 810-820 | 1951 | 11 |

| GP7 | 951-970 | 1951-1953 | 20 |

Fairbanks-Morse

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H24-66 (Train Master) | 850-861 | 1953-1956 | 12 |

| H16-44 | 930-935 | 1952 | 6 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 51-53 | 1948 | 3 |

Steam Roster

| Road Number | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| 4, 7 | Switcher | 0-4-0T |

| 8 | Switcher | 0-6-0T |

| 13-146 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| 151-185, 201-260 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| 301-399, 740-799, 821-899 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| 501-589 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| 801-820 | Twelve-Wheeler | 4-8-0 |

| 933-999 | American | 4-4-0 |

| 1001-1052 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| 1101-1193 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| 1151-1154 | Hudson | 4-6-4 |

| 1201-1262, 2101-2150 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| 1401-1454, 2201-2235 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| 1501-1505, 1601-1650 | Poconos | 4-8-4 |

A handsome A-B-B-A set of Lackawanna F units are eastbound at Binghamton, New York during the 1950s. In the lead is F7A #635 with an F7B, F3B, and F7A trailing. American-Rails.com collection.

A handsome A-B-B-A set of Lackawanna F units are eastbound at Binghamton, New York during the 1950s. In the lead is F7A #635 with an F7B, F3B, and F7A trailing. American-Rails.com collection.Conrail

While the railroad soldiered on it was dealt fatal blows during the 1970s; Hurricane Agnes hit the Northeast in June of 1972 causing flooding within many river valleys across New York and Pennsylvania.

By this date several smaller railroads were already in bankruptcy and the devastation wreaked havoc to EL’s lines forcing it into bankruptcy as well.

Two years later, on May 8, 1974 the Pougkeepsie Bridge, which spanned the Hudson River and provided for interchange with New England carriers like the New Haven, was severely damaged by fire.

Already in a precarious financial situation and unable to work out a deal with its unions for inclusion into the Chessie System (Chessie would have utilized all lines east of Sterling, Ohio) the company eventually decided to join the new Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail).

This system was already in the works to pick up the pieces of several bankrupt Northeastern lines, and agreed to take on the EL.

In the end, large sections of the "Friend Service Route" were abandoned under Conrail. However, today, much of the Lackawanna remains in use east of Binghamton, New York.

More Reading

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Ohio Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:40 PM

This information highlights the currently active Class 3 short lines operating within the state of Ohio. -

Pennsylvania Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:37 PM

Highlighted here is a complete list of active Class 3 short line railroads operating within the state of Pennsylvania. -

California Pumpkin Train Rides (2025): A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:25 PM

There is one location in California hosting the popular pumpkin train, at the Roaring Camp Railroads. Learn more about these event!