South Shore Line Railroad: Schedule, Map, Trains, Posters, Roster

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The South Shore Line, officially known as the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend Railroad (CSS&SB, was the most financially successful interurban of all-time). However, its early years were fraught with set backs as business never materialized.

The thought of complete shutdown was a real possibility when the property entered receivership in 1925. It was then that Samuel Insull's powerful empire gained control and set about a complete transformation of the property.

These efforts, and the interurban's ability to reach Chicago's Loop brought prosperity for the first time. Its freight and passenger traffic rapidly took off as profits soared.

The Great Depression caused Insull to lose control but the "South Shore Line" survived these lean years thanks to the precedents he had established.

As the years passed the CSS&SB increasingly lost its interurban traits. It so closely mirrored its larger counterparts that the Interstate Commerce Commission ended its classification as a traction carrier.

Today, the original CSS&SB is a memory but its successor still handles freight and the state-run Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (NICTD) continues providing passenger/commuter service.

South Shore Line R-2 boxcab #703 was photographed here at Hammond, Indiana with a short freight train on October 12, 1956. Author's collection.

South Shore Line R-2 boxcab #703 was photographed here at Hammond, Indiana with a short freight train on October 12, 1956. Author's collection.History

The South Shore Line was one of the few interurbans to enjoy many years of profitability. The company's early years, though, were a struggle.

It began as the Chicago & Indiana Air Line Railway, incorporated on December 2, 1901 to link East Chicago with South Bend, Indiana.

The road's promoters, a Cleveland syndicate led by J.B. Hanna, were well financed and by 1903, 3.4 miles had opened from East Chicago to Indiana Harbor.

That same year additional franchises were secured through Michigan City and South Bend, thus enabling completion of its charter as intended.

South Shore Line car #108 crosses the St. Joseph River along LaSalle Avenue in South Bend, Indiana on July 9, 1960. Author's collection.

South Shore Line car #108 crosses the St. Joseph River along LaSalle Avenue in South Bend, Indiana on July 9, 1960. Author's collection.Chicago, Lake Shore & South Bend

In 1904 a corporate name change took place when the C&IAL became the Chicago, Lake Shore & South Bend Railway (CLS&SB) to better reflect the company's intentions. During its construction high voltage, alternating current (AC) power was seen as the future in electrification.

It was developed, and championed, in the late 19th century by George Westinghouse as a substitute to General Electric's direct current technology.

Its advantages included fewer substations to maintain sufficient supply, voltage could be carried over long distances without power loss, and the availability of more powerful induction motors.

Logo

After consultants determined an AC system would yield considerable construction cost savings, a 6,600-volt, system was approved. As William D. Middleton notes in his book, "South Shore: The Last Interurban," only 700 volts were utilized in the cities of Gary, Michigan City, and South Bend for safety reasons.

While this drastic power difference was somewhat of an operational headache the real issue proved to be the heavier AC equipment, which substantially increased the cars' weight.

As management soon discovered, this considerably drove up operating and maintenance costs, which ultimately offset any savings derived during construction. Like the nearby Chicago, Aurora & Elgin, the CLS&SB was built to very high standards although did not employ third-rail.

Instead, it featured traditional overhead caternary supported by lineside poles with track speeds rated up to 75 mph. After the initial segment had been completed, work proceeded quickly to reach South Bend and regular service launched on September 6, 1908.

South Shore Line "800" #801 has a short freight on the new main line near East Chicago, Indiana on September 22, 1956. Author's collection.

South Shore Line "800" #801 has a short freight on the new main line near East Chicago, Indiana on September 22, 1956. Author's collection.Expansion

The CLS&SB had not been opened long when management recognized a direct entry into Chicago was needed. The western terminal of Hammond, Indiana was untenable; there simply was not enough traffic at this location to sustain the interurban. To achieve a Windy City connection, an agreement was reached with Illinois Central to lease its subsidiary, the Kensington & Eastern.

This short, electrified system connected with the IC's downtown Chicago line at Pullman, running east to an interchange with the CLS&SB at Hammond. It opened for service on April 4, 1909.

At A Glance

While the new connection did not provide direct, point-to-point service into Chicago, the two roads did offer fluid schedules which enabled passengers to reach Illinois Central's downtown stations at Van Buren and Randolph Streets.

The CLS&SB's entire corridor was 91 miles although as W. Donald Allison's article, "The Railroad With Orange Trains" from the May, 1953 issue of Trains Magazine points out, only the 69.5 miles from Hammond to South Bend was under its direct ownership.

Unfortunately, lack of through, single-seat service continued to hamper ridership. To make matters worse the road's final construction cost of $4.5 million was nearly double that originally estimated and planners had not even bothered to develop carload freight business (they were finally launched in 1916).

South Shore Line steeple cabs #1008 and #1002 have a short extra at Burnham, Illinois on September 24, 1955. Author's collection.

South Shore Line steeple cabs #1008 and #1002 have a short extra at Burnham, Illinois on September 24, 1955. Author's collection.Insull Era

Ownership's frustration began to set in as the system sank deeper into red ink, earning a return of less than 1%. It saw some growth during World War I but the 1920's were a further struggle.

By 1924 it had posted a net deficit of $1.7 million and those in control wanted out. At this time Samuel Insull became interested, recognizing the property's potential.

Insull was born in London, England on November 11, 1859 to a modest family. He took his first job at 14, and then found employment as a switchboard operator with a Thomas Edison-owned company in London during 1889.

When he was 21, he immigrated to the United States to continue his employment duties within the Edison companies and slowly worked his way up through the ranks.

He rose to vice-president within the recently created General Electric but after not achieving the presidency moved on to another new firm, the Chicago Edison Company.

Through the end of the 19th century and beyond, Insull became an industry leader in the utilities field of natural gas and electricity. He also believed that electrified railroads, notably interurbans, were the future in transportation.

As Larry Plancho notes in his book, "The Story Of The Chicago Aurora & Elgin Railroad, 2 - History," Insull was regarded as fair-minded and believed in providing top quality service for his customers.

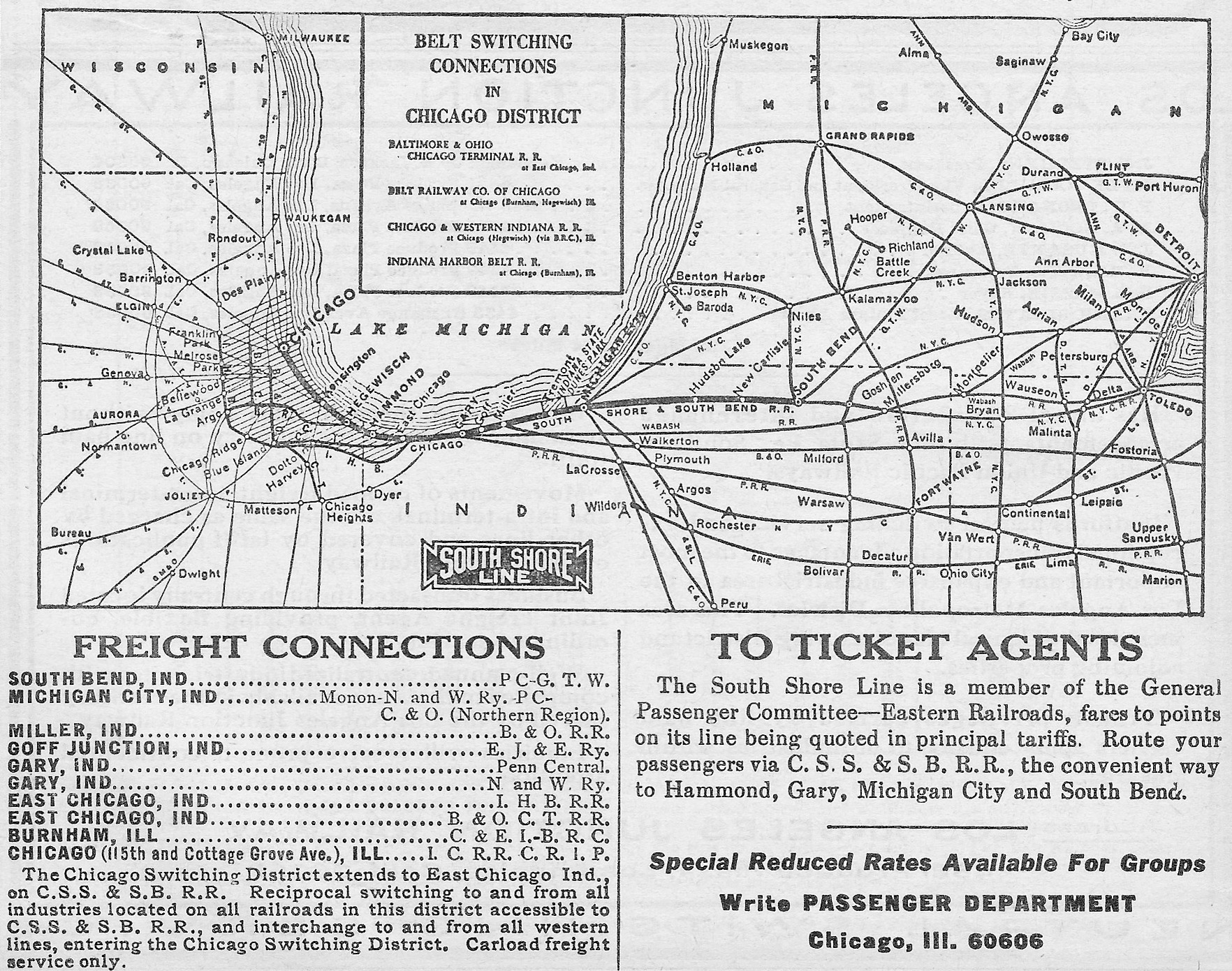

System Map (1969)

An official, 1969 system map of the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend Railroad. Author's collection.

An official, 1969 system map of the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend Railroad. Author's collection.During the height of his empire he held properties in 32 states with assets totaling more than $2 billion. Among his interurban portfolios, he controlled Chicago's primary three: the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee; Chicago, Aurora & Elgin; and the South Shore.

To necessitate takeover of the latter it was placed into receivership on February 28, 1925. A few months later a new company was incorporated on June 23rd; known as the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend Railroad it acquired the former CLS&SB assets.

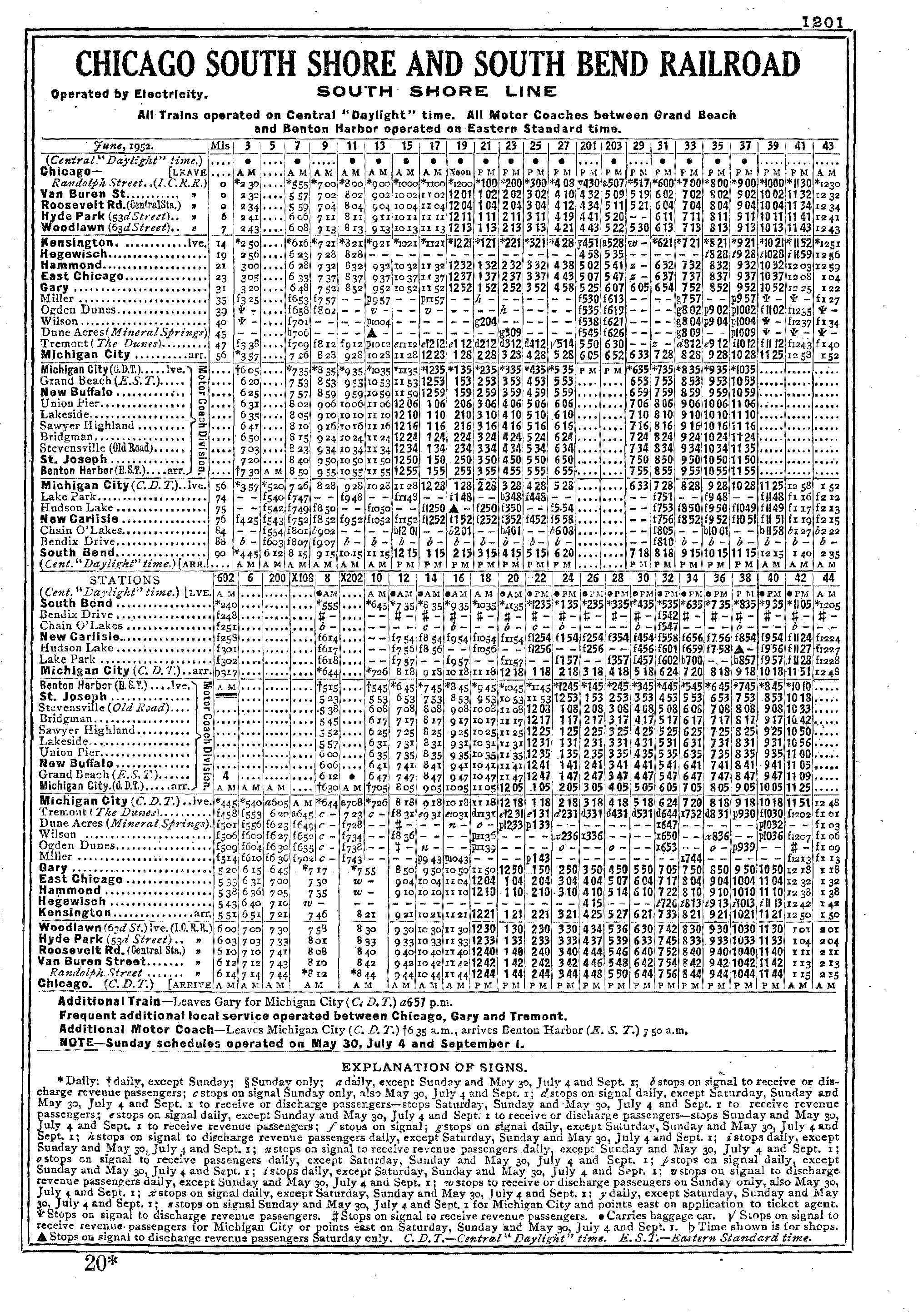

Timetable and Schedules (1952)

Typical of Insull's belief in high quality service, new management immediately went to work overhauling the system.

The more notable improvements included pouring tons of fresh ballast, laying 100 pound rail in place of the original 70-80 pound variety, installing new ties, purchasing new steel cars from Pullman, overhauling the signaling system, and tying in high-speed turnouts.

Due to the predecessor's poor financial situation it had been unable to carry out even basic maintenance such as weed control. Insull's group quickly recognized the major impediment to growth was lack of through service into Chicago.

A pair of South Shore Line R-2 boxcabs (ex-New York Central) tote a single boxcar down Orange Street, at the intersection of Huey Street, in South Bend, Indiana on May 10, 1964. The locomotives are probably either coming from, or going to, switch a local customer, H.B. Fuller, just a few hundred feet behind the boxcar to the right. Author's collection.

A pair of South Shore Line R-2 boxcabs (ex-New York Central) tote a single boxcar down Orange Street, at the intersection of Huey Street, in South Bend, Indiana on May 10, 1964. The locomotives are probably either coming from, or going to, switch a local customer, H.B. Fuller, just a few hundred feet behind the boxcar to the right. Author's collection.A fortuitous situation presented itself when, at the same time, Illinois Central was finishing an electrification project of its suburban lines to satisfy a city ordinance. The two quickly worked out a plan whereby South Shore trains would utilize IC trackage rights directly into its Randolph Street Station.

However, to operate within this territory meant adopting IC's 1,500-volt, direct-current system. Work proceeded quickly to retire the 6,600-volt AC operation and the new DC electrification was ready for service by July of 1926. There were a total of eight substations constructed to supply power.

These buildings were located at Hammond, Gary, Michigan City, New Carlisle, Ogden Dunes, South Bend, Tee Lake, and Tremont. South Shore trains began rolling into downtown Chicago on August 29th. The effects were immediate although it was the following year which truly told the story as passenger business more than doubled that of 1926 levels.

The Insull team, between upgrades and conversion to DC operation, had invested more than $6.5 million into the interurban. To further enhance demand, parlor cars, and even dining services, were introduced in 1927. The company also launched the Shore Line Motor Coach Company to funnel additional business to its trains.

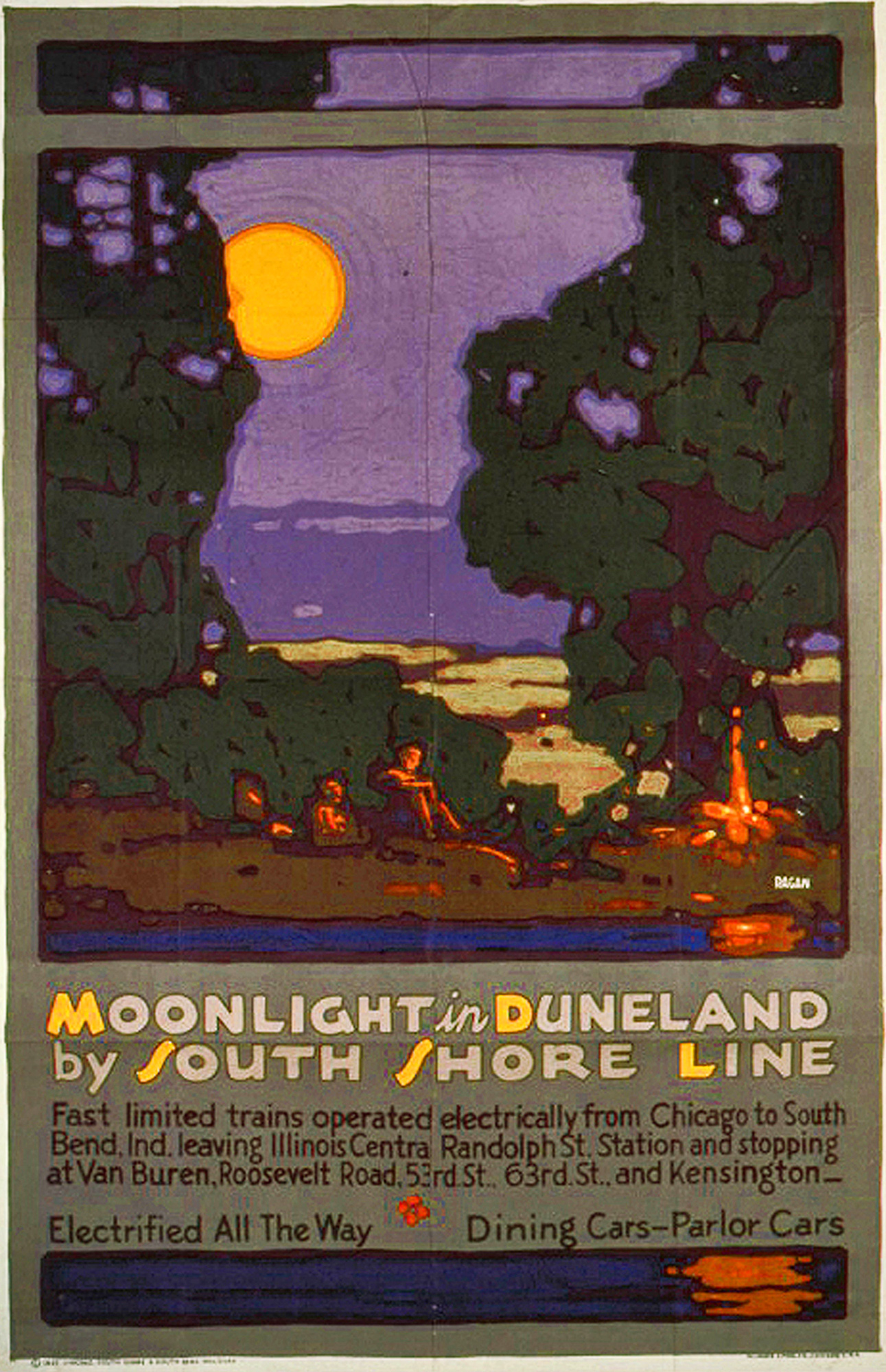

Posters

After Insull acquired the South Shore Line the company spent a great deal of resources promoting its services to boost both freight and passenger business.

There were considerable newspaper advertisements, booklets, and even an accurate, operable scale model produced for this purpose.

None, however, were more eye-catching than the vivid lithographic posters created by several Chicago artists. These pieces were commissioned to attract attention while increasing ridership, and that they did!

The most-often featured location was Indiana's popular Dunes along the southern shores of Lake Michigan. The area somewhat resembles coastal beaches in the Southeast and the South Shore Line went to great lengths in helping the state preserve this natural wonder.

Eventually, the Indiana Dunes State Park was established which is today part of the much larger, federally protected Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

To see wonderful reproductions of these striking works of art pick up a copy of, "Moonlight In Duneland: The Illustrated Story Of The Chicago South Shore And South Bend Railroad," by Ronald Cohen and Stephen McShane.

South Shore Line MU combine #100 receives a bath at the shops in South Bend, Indiana on June 25, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line MU combine #100 receives a bath at the shops in South Bend, Indiana on June 25, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.By 1928 the South Shore Line was boasting gross revenues of over $3 million, a more than three-fold increase from the years leading up to Insull control.

There was also a concentrated effort at expanding freight operations, a tactic which had proved modestly successful on the nearby North Shore Line and CA&E.

During the latter 1920's a series of 80 and 85-ton steeple-cab motors arrived from Baldwin/Westinghouse for this purpose but just as this was getting underway, the Great Depression hit in October of 1929.

The proceeding economic downturn caused Insull to lose control in 1932 after his companies tumbled into bankruptcy and South Shore soon followed, entering receivership on September 30, 1933.

New management carried on Insull's practices and by decade's end things had stabilized. In 1938 the company exited receivership as it took on a greater role in moving freight.

After the United States entered World War II this business was totaling nearly $2 million annually, a number that had reached $3.5 million by 1950.

Like the standard railroads, the South Shore Line struggled to meet passenger demands during the conflict, an issue made more difficult by the fact that it was unable to purchase new equipment.

Officials came up with an interesting but effective solution. Its primary shops in Michigan City, Indiana simply rebuilt the fleet, increasing car lengths to accommodate more seating.

By the postwar years the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend Railroad was more closely resembling its larger counterparts and losing its identity as a diminutive, lightly-trafficked interurban.

As the passenger business became increasingly unprofitable, management realized the road's future lay in freight. To accommodate growing traffic it picked up three monstrous 2-D+D-2 motors from General Electric in 1949.

These machines weighed 273 tons and were rated at more than 5,000 horsepower. The fleet of twenty had originally been destined for the Soviet Union but could not be delivered following the Cold War's outbreak.

They are most famous for their time spent on the Milwaukee Road where, known as "Little Joes," they proved quite adept at handling either freight or passenger consists through the northern Rocky Mountains in western Montana and Idaho's Northern Panhandle. The South Shore's trio, regarded as "800's" (since they were placed within the 800 Class, numbered #801-803), proved just as skilled.

As Mr. Allison's article notes they could easily pull whatever tonnage required while cruising at 45 mph. During the latter 1950's the big motors were complemented by a group of six, 140-ton C-C electrics purchased second-hand from the New York Central.

The former NYC "R-2's" were placed within the 700 Class and their beefy 3,000 horsepower allowed for retirement of the remaining steeple-cabs. Aside from its passenger situation the South Shore Line faced another issue during the 1950's. When originally constructed the interurban had, like many others, simply placed its right-of-way directly through city streets.

This became an operational nightmare in East Chicago where there were so many trains during a typical weekday that one passed through the busy streets regularly, every hour.

It not only became an extreme annoyance to locals but also greatly bottlenecked rail operations. To alleviate the problem an extensive bypass was constructed, which opened in late 1956.

The last years of South Shore's independence were a roller coaster. The company continued to maintain a strong freight business thanks to the heavy industrialized regions of northwestern Indiana and South Chicago (it had surpassed $4 million by the early 1960's) but the passenger situation was becoming intolerable.

In 1958 deficits had grown to $719,000 and the red ink had more than tripled by the 1970's. The situation was further complicated by the need to retire its aging Pullman equipment but there was no funds to do so. On January 3, 1967 the Chesapeake & Ohio acquired the South Shore Line for its freight business.

While Chessie's ownership lasted only a little more than a decade it brought diesels to the property for the first time when first-generation GP7's arrived followed by brand new GP38-2's in 1981. Today, the latter remain in service. Freight electrification ended on January 31, 1981 when "800" #803 made its final run.

South Shore Line MU coach #1, manufactured by Pullman in 1926, was photographed here at Michigan City, Indiana on August 9, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line MU coach #1, manufactured by Pullman in 1926, was photographed here at Michigan City, Indiana on August 9, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Equipment

Chicago & Indiana Air Line Railway

| Car Number(s) | Builder | Type | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | J.G. Brill | Two-Truck Trolley Car | 1903 |

Chicago, Lake Shore & South Bend Railway

| Car Number(s) | Builder | Type | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-24 | Niles | MU Coach | 1908 |

| 75-77 | Niles | MU Combine | 1908 |

| 101-110 | G.C. Kuhlman | MU Coach-Trailer | 1908 |

Not included here are a handful of second-hand coaches picked up from the Santa Fe around 1917.

Chicago, South Shore & South Bend

| Car Number(s) | Builder | Type | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-25 | Pullman | MU Coach | 1926-1927 |

| 26-40 | Standard Steel | MU Coach | 1929 |

| 100-110 | Pullman | MU Combine | 1927 |

| 111 | Standard Steel | MU Combine | 1929 |

| 201-212 | Pullman | MU Coach-Trailer | 1927-1929 |

| 301-302 | Pullman | MU Diner | 1927 |

| 351-352 | Pullman | MU Parlor-Buffet | 1927 |

| 353-354 | Standard Steel | MU Parlor-Buffet | 1929 |

Electric Locomotive Roster

Chicago, Lake Shore & South Bend Railway

Under the CLS&SB, management did not bother establishing a carload freight business for more than a decade even though it was located within a region that carried a great deal of industrial development.

It finally launched freight service on August 1, 1916, which was rapidly expanded upon by the Insull interests.

| Number(s) | Builder | Model Type | Horsepower | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 505-506 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Boxcab (B-B)/72-Ton | 680 | 1916 |

Chicago, South Shore & South Bend

| Number(s) | Builder | Model Type | Horsepower | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 701-707 | Alco/GE | Box-Cab (C-C)/140-Ton | 3,000 | *Ex-New York Central |

| 801-803 | General Electric | Double-End (2-D+D-2)/273-Ton | 5,120 | 1949 |

| 901-904 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/97-Ton | Unknown | **Ex-Illinois Central |

| 1001-1004 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/80-Ton | 1,600 | 1926 |

| 1005-1006 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/53-Ton | Unknown | ***1927 |

| 1007-1010 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/80-Ton | 1,600 | 1928 |

| 1011-1013 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/85-Ton | 1,600 | 1929-1930 |

| 1014 | Baldwin/Westinghouse | Steeple-Cab (B-B)/80-Ton | 1,600 | 1931 |

* Built in 1930-1931 for the New York Central, listed as Class R-2. Rebuilt by South Shore Line's Michigan City Shops between 1955-1958.

** Built in 1929, acquired from the IC in 1941 to handle wartime traffic.

*** Sold to the Niagara Junction Railway where they became #8-9.

Diesel Roster

Chicago, South Shore & South Bend

| Model | Builder | Number(s) | Horsepower | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP38-2 | Electro-Motive | 2000-2009 | 2,000 | 1981 |

| SD38-2 | Electro-Motive | 804-805 (Formerly 154-155) | 2,000 | *1978 |

* Originally built for Reserve Mining in 1978 as #1239 and #1230.

Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (NICTD) Roster

| Car Number | Builder | Type | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-44 | Nippon Sharyo (Japan) | MU Coach | 1982-1983 |

The above roster information is not quite complete but is presented with the best information available. All information courtesy of the following resources:

Middleton, William D. South Shore: The Last Interurban. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999 edition.

Middleton, William D. Traction Classics: The Interurbans, Extra Fast And Extra Fare. San Marino: Golden West Books, 1985.

South Shore Line R-2 boxcabs and an "800" motor, #803, at the interurban's shops in Michigan City, Indiana in June, 1960. The R-2's had been acquired in the latter 1950's from the New York Central. Author's collection.

South Shore Line R-2 boxcabs and an "800" motor, #803, at the interurban's shops in Michigan City, Indiana in June, 1960. The R-2's had been acquired in the latter 1950's from the New York Central. Author's collection.Today

Three years later, in September of 1984, the C&O, which was transitioning to create CSX Transportation, sold the South Shore Line to a private group, the Venango River Corporation. This new ownership survived for only a few years when it encountered bankruptcy in 1989.

The railroad's freight operations were then acquired by the Anacostia & Pacific which formed the Chicago, SouthShore & South Bend Railroad on January 1, 1990.

During this process the publicly-funded Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (NICTD) had been attempting to purchase the property for a decade to maintain commuter service.

It was finally able to do so following Venango's bankruptcy. Under the current agreement, NICTD owns all trackage and facilities while Anacostia & Pacific has exclusive access for freight services and directly owns the former K&E trackage (purchased from Illinois Central in 1996).

Today, the A&P notes its traffic base consists of "chemicals, coal, grain, manufactured products, paper, pig iron, steel, and roofing materials."

And so, as it has done for over a century, "America's Last Interurban" soldiers on moving both freight and passengers across northern Indiana. To learn more about today's modern South Shore Line commuter system please click here.

Photo Gallery

South Shore Line coach #17 was photographed here at Gary, Indiana on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line coach #17 was photographed here at Gary, Indiana on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection. South Shore Line coach #30 and an express trailer are tied down at the Randolph Street Station in Chicago on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line coach #30 and an express trailer are tied down at the Randolph Street Station in Chicago on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection. South Shore Line coach #38 was photographed here at Gary, Indiana on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line coach #38 was photographed here at Gary, Indiana on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection. South Shore Line's yard in Gary, Indiana, as seen from the end of the station platform on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

South Shore Line's yard in Gary, Indiana, as seen from the end of the station platform on September 11, 1960. American-Rails.com collection.Contents

Chicago, Lake Shore & South Bend

Timetable and Schedules (1952)

Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District (NICTD) Roster

Recent Articles

-

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad. -

Delaware Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:23 PM

Delaware may rank 49th in state size but has a long history with trains. Today, a few museums dot the region. -

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here.