Belt Railway Of Chicago: Map, Roster, Logo, History

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Belt Railway of Chicago has been an integral part of the region's transportation network since the early 1880s. It was

formed by a growing need to provide efficient interchange services at America's railroad capital.

The company's heritage begins with the Chicago & Western Indiana, itself a belt line of sorts. Over time, the property was acquired by numerous railroads giving it the greatest number of Class I connections.

The move enabled these carriers to utilize the Belt Railway for interchanging and transferring their freight through and within the city rather than doing so themselves.

Today, it continues to function much as did a century ago despite many mergers and bankruptcies of the big roads.

History

For railfans, it is best known for once utilizing a large fleet of historic Alco diesels. Today, these belching beasts are no longer on the property as the railroad maintains a fleet of entirely second-generation Electro-Motive products (some rebuilt to environmentally-friendly specifications) and low-emission "gensets."

Photos

Another set of Centuries assemble their train of coal hoppers in South Chicago on October 6, 1996. These units soldiered on for several decades before finally being retired. Wade Massie photo.

Another set of Centuries assemble their train of coal hoppers in South Chicago on October 6, 1996. These units soldiered on for several decades before finally being retired. Wade Massie photo.Chicago & Western Indiana

The Belt Railway of Chicago is the city's oldest belt line, formed by the Chicago & Western Indiana.

The C&WI's history begins on June 6, 1879 when it was chartered by John B. Brown and a few business partners. With an ever-increasing number of railroads reaching the Windy City they realized a terminal line would be of great benefit.

In less than a year the C&WI had connected Dolton and an interchange with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois (22 miles).

This gave it connections with:

- Illinois Central

- Michigan Central

- Santa Fe

- Wabash

- Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago (a Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary)

- St. Charles Air Line

- Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (Rock Island)

During January of 1882 the C&WI continued expanding by acquiring the Chicago & Western Indiana Belt Railway and South Chicago & Western Indiana pushing its western reach to Hammond, Indiana just across the state line.

Along the way additional interchange commenced with the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway (an early Milwaukee Road predecessor), Nickel Plate Road, Monon, Erie, and again with the Santa Fe and Wabash.

A pair of Belt Railway of Chicago C424s move away from the photographer in December, 1979. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Belt Railway of Chicago C424s move away from the photographer in December, 1979. American-Rails.com collection.Prior to construction of Dearborn Station the C&WI was acquired by a consortium of railroads as both a means of reaching this future facility and helping to facilitate its funding; their financial assistance also provided the much-needed access they so desired into downtown Chicago.

This original group included the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago (Monon); Chicago & Atlantic (Erie); Chicago & Eastern Illinois; Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific (Wabash); and Grand Trunk Railway (predecessor of the Grand Trunk Western).

The C&WI was given actual ownership of Dearborn although future owner Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe stands as the most visually prominent.

Between 1912 and 1933 the C&WI picked up two other small additions, the Chicago Union Transfer Railway (more about this operation later) and Burlington South Chicago Terminal Railroad.

During the company's peak period it maintained fourteen different interlocking towers and owned a total of nearly 152 miles of track which included all through routes, yards, sidings, spurs, etc.

Logo

In the late steam era it operated nearly 100 locomotives with the largest being 2-10-2's. Beginning in the late 1940's it began purchasing diesels from Electro-Motive and American Locomotive to replace its steam fleet (switchers and light road-switchers).

It even sported its own livery of black and yellow. While the C&WI did host some freight services most of this was handled through its Belt Railway of Chicago affiliate, which utilized trackage rights for this purpose.

Its primary role was to switch passenger trains and keep rail operations flowing smoothly in and out of Dearborn. During its final days its owners had dwindled to just the Santa Fe, Erie Lackawanna, Grand Trunk Western, Louisville & Nashville, and Norfolk & Western.

Following the creation of Amtrak in May of 1971 the new carrier abolished operations at Dearborn in favor of nearby Union Station thus making the C&WI redundant.

After that point the company functioned primarily on paper as the Belt Railway took over its trackage for freight services. It remained a corporate entity until 1994.

The Belt Railway's TR4 "cow-calf" set works Clearing Yard at Bedford Park, Illinois on October 5, 1996. Wade Massie photo.

The Belt Railway's TR4 "cow-calf" set works Clearing Yard at Bedford Park, Illinois on October 5, 1996. Wade Massie photo.Creation

While the Chicago & Western Indiana was just getting under way John Brown recognized a true belt line would be beneficial to serve the numerous railroads entering Chicago. Unlike the C&WI, which provided access to only a limited number, the new operation would, in theory, serve everyone.

This would eliminate the need of these larger systems to build separate rights-of-way into the city. Inevitably, distrust among them continued for years until the big carriers finally came to their senses in the 20th century.

According to Jerry Pinkepank's article, "How The Belt Came To Be" from the October, 1966 issue of Trains Magazine, the Belt Railway of Chicago's history begins in early 1881 when Brown chartered what was then known as the Belt Division, Chicago & Western Indiana Railroad.

Construction began later that year and proceeded quickly; to the east the road partially utilized trackage rights over the C&WI before turning west through Forest Hill and Hayford.

The route then swung northward to Cicero with intentions of reaching the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul at Cragin Junction in Jefferson, Illinois. Here, a serious disagreement ensued with the community concerning a crossing right-of-way.

During a time in which railroads sometimes took the law into their own hands, tracks were ultimately built over the crossing without permission.

After carrying out this rogue operation the company successfully received an injunction to prohibit their removal. As a result, the Belt Division was deemed complete by August of 1883.

While the project was under construction the consortium which controlled the C&WI also took over (via lease) the Belt Division in October of 1882.

It was subsequently renamed the Belt Railway Company of Chicago and then proceeded to build its own line into South Chicago, which ended the need to operate over the C&WI.

From this early period the BRC tried to bring in more railroads but none signed on. Their eventual interest was due to Clearing Yard. Today, this important facility, located in Bedford Park, was the idea of Alpheus Beede (A.B.) Stickney.

He is best known for establishing the Chicago Great Western and conceived Clearing as Chicago's primary classification yard.

It would be owned by all the belt lines (effectively, all Chicago railroads) and feature a unique, circular design. Trains would enter the yard, operate around the loop, drop off/pick up cars, and then be on their way in what was perceived as an efficient means of fluidity.

At A Glance

Clearing Yard - Cicero - Cragin Clearing Yard - Hayford - Forest Hill - South Chicago - South Deering Hammond Junction - Pullman | |

The yard was even operated by its own company, the Chicago Union Transfer Railway, incorporated in 1889. The huge terminal opened in 1902 but, unfortunately, lack of traffic and mistrust among the bigger railroads killed Stickney's plan.

When finally constructed it also never carried the circular pattern but was instead built as a hump yard, one of the first of its type. It sat vacant almost immediately and remained so for a decade until congestion became so severe railroads were essentially forced to use it.

By this time other belts had sprung up, notably the B&O-controlled Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal, the Indiana Harbor Belt (New York Central and Milwaukee Road), and to a lesser extent the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern. However, they could not keep up with the overflowing business.

Finally, common sense prevailed and nine additional owners joined the original five in 1912 in what was known as the Belt Operating Agreement.

The new railroads included:

- Burlington

- Chesapeake & Ohio

- Chicago & Alton

- Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha (C&NW)

- Illinois Central

- Pennsylvania

- Rock Island

- Santa Fe

- Soo Line

The C&A and CStPM&O later sold their stakes. In addition, the Pere Marquette purchased an interest in 1924 but was then acquired by the C&O in 1947.

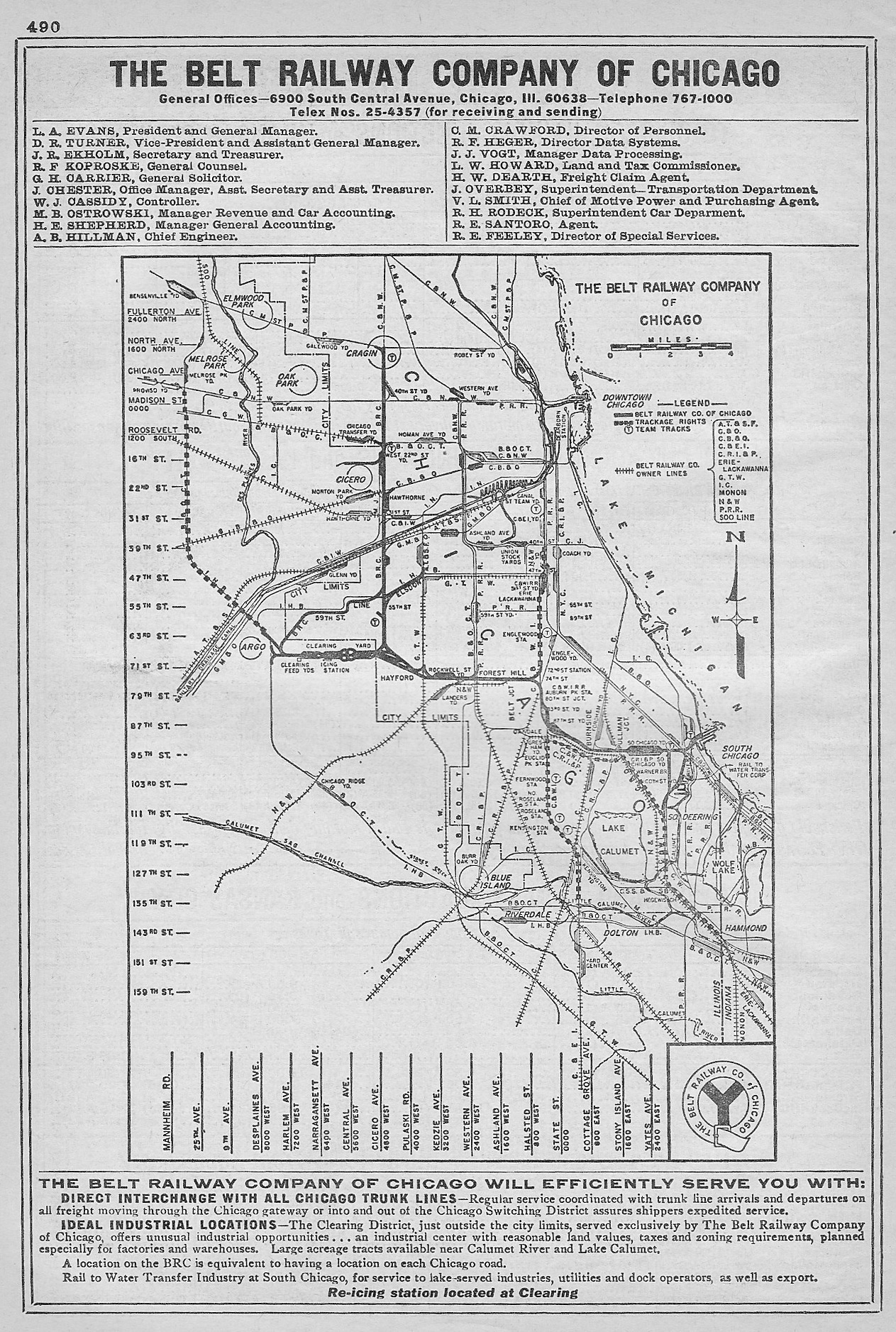

System Map (1969)

After this time the twelve predominant owners remained unchanged until the postwar years witnessed numerous mergers and consolidations.

Following the 1912 agreement Clearing Yard was again rebuilt to handle more capacity (from 5,000 cars in 1902 to 10,000 by 1914) where it became the world's longest freight yard at 5 miles.

It held this distinction until the PRR's Conway facility was greatly expanded during the 1950's.

To offer the best means of switching and efficient traffic flow a new rail line was built west of the yard which connected to the IHB and B&OCT then looped northeastward along 59th Street before rejoining the Belt Railway's main line to Cragin Junction.

Over the years Clearing has been continually rebuilt and expanded. Today, according to the railroad it is now 5 1/2 miles in length, covers 786 acres, and can classify "40 and 50 miles of train consists every 24 hours."

In short, the yard best describes BRC's purpose which is to sort and classify inbound traffic and, if not terminating in the city, move it out of Chicago as quickly as possible.

Mr. Pinkepank's article from the September, 1966 issue of Trains Magazine entitled "The Belt Railway Of Chicago: A Railroad's Railroad," explained best how it all worked (If you have can find copies both of his articles mentioned here they provide a superb history regarding the BRC!).

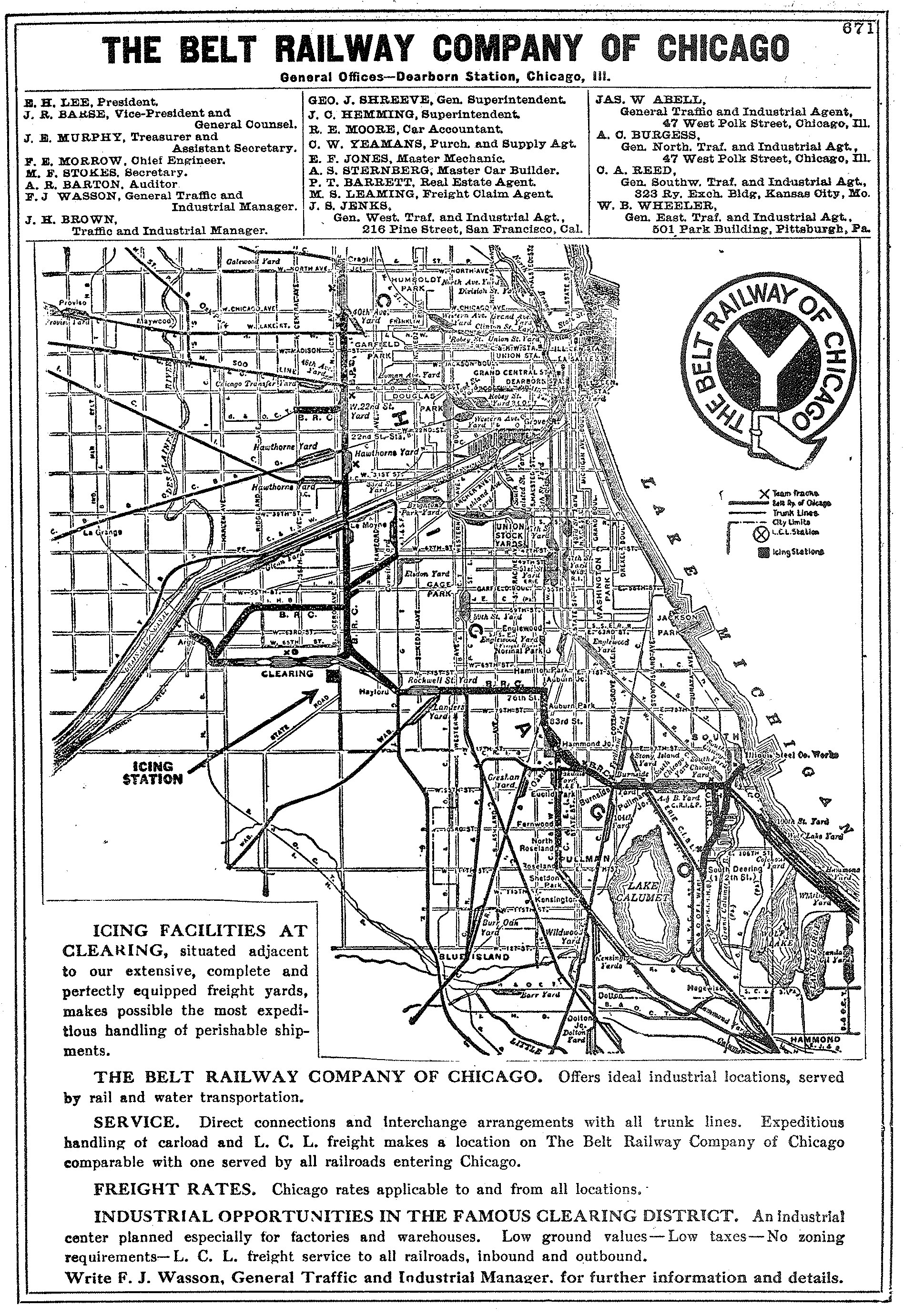

System Map (1930)

The big railroads constructed so-called "perimeter yards" around the city and from these freight was picked up by the belt lines which transferred it either through the city or to its final destination.

The trunk lines could do so on their own via what was known as direct interchange albeit, generally, the belts were more efficient and removed this hassle. As for Clearing Yard it grew into more than just a classification facility.

At its northern periphery a real estate developer created the Clearing Industrial District (now known as the Bedford-Clearing Industrial District) which witnessed numerous factories spring up that generated a substantial amount of originating freight. Business here has cooled but not entirely disappeared.

The Belt Railway remained a strong, healthy system until problems began in the postwar years when mergers dwindled its need and some owners simply vanished. In 1962 the original 50-year operating agreement had expired, which allowed the Class I's to assume direct ownership by purchasing the C&WI's interest.

Diesel Roster

For a current diesel locomotive roster please click here.

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH-600 | 300, 302-303 | 1934-1935 | 3 |

| S1 | 304-306 | 1941-1942 | 3 |

| S2 | 400, 403-404, 406-411 | 1941-1950 | 9 |

| S6 | 420 | 1957 | 1 |

| RS2 | 450-458 | 1949 | 9 |

| C424 | 600-605 | 1965-1966 | 6 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | 401-402 | 1942-1944 | 2 |

| DS-4-4-1000 | 405 | 1947 | 1 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP7 | 470-477 | 1951-1952 | 8 |

| GP9 | 471 (Second), 480-481 | 1956-1958 | 3 |

| GP38-2 | 490-495 | 1972 | 6 |

| TR2 | 500A-501A (Cow), 500B-501B (Calf) | 1949 | 4 |

| TR4 | 502A-506A (Cow), 502B-506B (Calf) | 1950 | 10 |

| SW9 | 520-523 | 1951 | 4 |

| SW1200 | 524-526 | 1963 | 3 |

| SW1500 | 530-532 | 1967-1968 | 3 |

| MP15DC | 533-536 | 1975-1980 | 4 |

General Electric/Ingersoll-Rand

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boxcab | 301 | 1930 | 1 |

Steam Roster

The Belt Railway completed its switch from steam to diesel power on January 20, 1952.

| Class | Wheel Arrangement | Road Number(s) | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0-6-0 | 1-12 | Pittsburgh | 1882 |

| None | 4-4-0 | 13-17, 20 | Rhode Island | 1884-1887 |

| None | 4-4-0 | 18-19 | Baldwin | 1892 |

| None | 0-6-0 | 21-23 | Rhode Island | 1888 |

| None | 0-6-0 | 24-40 | Schenectady | 1889-1892 |

| D-2 | 0-6-0 | 41-45 | Cooke | 1892 |

| E-1 | 0-6-0 | 46-49 | Richmond | 1900 |

| E-2 | 0-6-0 | 50-69 | Alco | 1903 |

| E-3 | 0-6-0 | 70-79 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| E-4 | 0-6-0 | 80-89 | Alco | 1906 |

| G-1 | 0-8-0 | 90-99 | Alco | 1910 |

| G-2 | 0-8-0 | 100-109 | Lima | 1911 |

| H-1 | 0-8-0 | 110-114 | Baldwin | 1913 |

| J-1 | 0-8-0 | 120-124 | Baldwin | 1923 |

| J-2 | 0-8-0 | 125-128 | Baldwin | 1925 |

| K-1 | 0-8-0 | 129-133 | Baldwin | 1927 |

| K-2 | 0-8-0 | 134-138 | Baldwin | 1927 |

| K-3 | 0-8-0 | 139-143 | Baldwin | 1928 |

| K-4 | 0-8-0 | 144-148 | Baldwin | 1930 |

| M | 0-8-0 | 150 | Baldwin | 1925 |

| C-1 | 2-10-2 | 1-5 | Baldwin | 1918 |

| C-2 | 2-10-2 | 20-24 | Alco | 1918 |

Steam Roster (Chicago Union Transfer Railway)

| Class | Wheel Arrangement | Road Number(s) | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0-6-0 | 1-2 | Cooke | 1902 |

| None | 0-6-0 | 3-6 | Dickson | 1902 |

| None | 2-8-0 | 101-104 | Alco | 1902 |

| None | 0-4-4T | 51-52 | Baldwin | 1891 |

The above steam roster information is courtesy of Jerry Pinkepank's article, "How The Belt Came To Be" from the October, 1966 issue of Trains Magazine.

Belt Railway GP7 #471 still looks like new as it works Clearing Yard on October 5, 1996. Wade Massie photo.

Belt Railway GP7 #471 still looks like new as it works Clearing Yard on October 5, 1996. Wade Massie photo.Today

By the late 1980's the company was owned by just the Santa Fe, Burlington Northern, Conrail, CSX Transportation, Illinois Central Gulf, Grand Trunk Western, Norfolk Southern, Union Pacific, and Soo Line.

Unfortunately, the mergers also meant the other big belts were now essentially owned by the same railroads (CSX also controlled the B&OCT and Conrail the IHB). Additionally, intermodal was on rise and industrial business decline. Combined, this meant the BRC's need was simply in decline.

The railroad was successful in having some owners close their surrounding yards and transfer their operations to Clearing. Alas, by 1990 the yard sat dangerously empty.

As Michael Blaszak's article, "Belt Railway Of Chicago: Back From the Brink" from the July, 1993 issue of Trains Magazine notes, new management arrived just in time and the company eventually got back onto its feet.

Today, six of the seven Class I railroads still own the terminal line including CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern, BNSF, Union Pacific, Canadian National, and Canadian Pacific.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Illinois Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 29, 25 10:28 AM

This information denotes all active Class 3 short line railroads currently operating throughout the state of Illinois. -

Delaware Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 29, 25 10:24 AM

This article details the currently active short line railroads (Class 3s) found in the state of Delaware. -

Idaho Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 29, 25 10:22 AM

Presented here is a complete list of active short line railroads operating within the state of Idaho.