Railroads In The Gilded Age (1880s)

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

With the Transcontinental Railroad's completion, ever greater numbers of Americans headed west for new opportunities and a fresh start.

Most new rail construction through the mid-1870's had been concentrated predominantly east of the Mississippi River.

However, as folks headed west, the iron horse followed. The building boom peaked during the 1880's, during the height of the Gilded Age.

As historian John F. Stover notes in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," a staggering 70,400 miles was laid down between 1880 and 1890 with total mileage growing from 93,200 to 163,600!

The West, alone, witnessed a staggering 129% increase. The decade also witnessed many improvements in passenger comfort and greater operational efficiencies.

Images

Importance

These included:

- Adoption of a Standard Time in 1883

- Increased use of the knuckle-coupler and automatic air brake (while these two devices would not be federally mandated until the 1890s at least one state would required their use on all trains operating within its borders during the decade)

- Implementation of a uniform track gauge (4 feet, 8 1/2 inches)

- Introduction of central heating

The information here provides a brief history of the industry during the 1880's.

At A Glance

93,267 Miles (1880) | |||||

Greater Use Of MCB Coupler (Automatic Coupler) Standard Gauge Achieved (Adopted by Master Car Builder's Association) |

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

The Gilded Age witnessed several railroads complete their trunk lines:

- The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe reached California in 1883 when its leader, William Barstow Strong, successfully broke Southern Pacific's monopoly within the Golden State

- The Erie Railroad (then known as the New York, Lake Erie & Western) pulled off an incredible feat by reaching Chicago through acquisition of the Chicago & Atlantic Railway in 1883.

After years of delays and financial troubles the Northern Pacific Railway opened the first transcontinental route into the Pacific Northwest in 1883 (initially via the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company, it would not gain a direct route to Puget Sound until 1888).

In late 1882 components of what later became the modern Denver & Rio Grande Western (the Denver & Rio Grande and original Denver & Rio Grande Western) opened a corridor through the heart of the Rocky Mountains between Denver and Salt Lake City.

Finally, the Southern Pacific arrived at El Paso, Texas in 1881 and shortly thereafter (via several subsidiaries which later became its Texas & New Orleans) opened a through route to New Orleans, Louisiana (the fabled "Sunset Route").

These are only a fraction of the decade's major accomplishments but highlight just how much construction was ongoing at the time.

As Dr. George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the railroad industry was nearing its "economic maturation" by the 1870's, a process virtually completed by the 1880's.

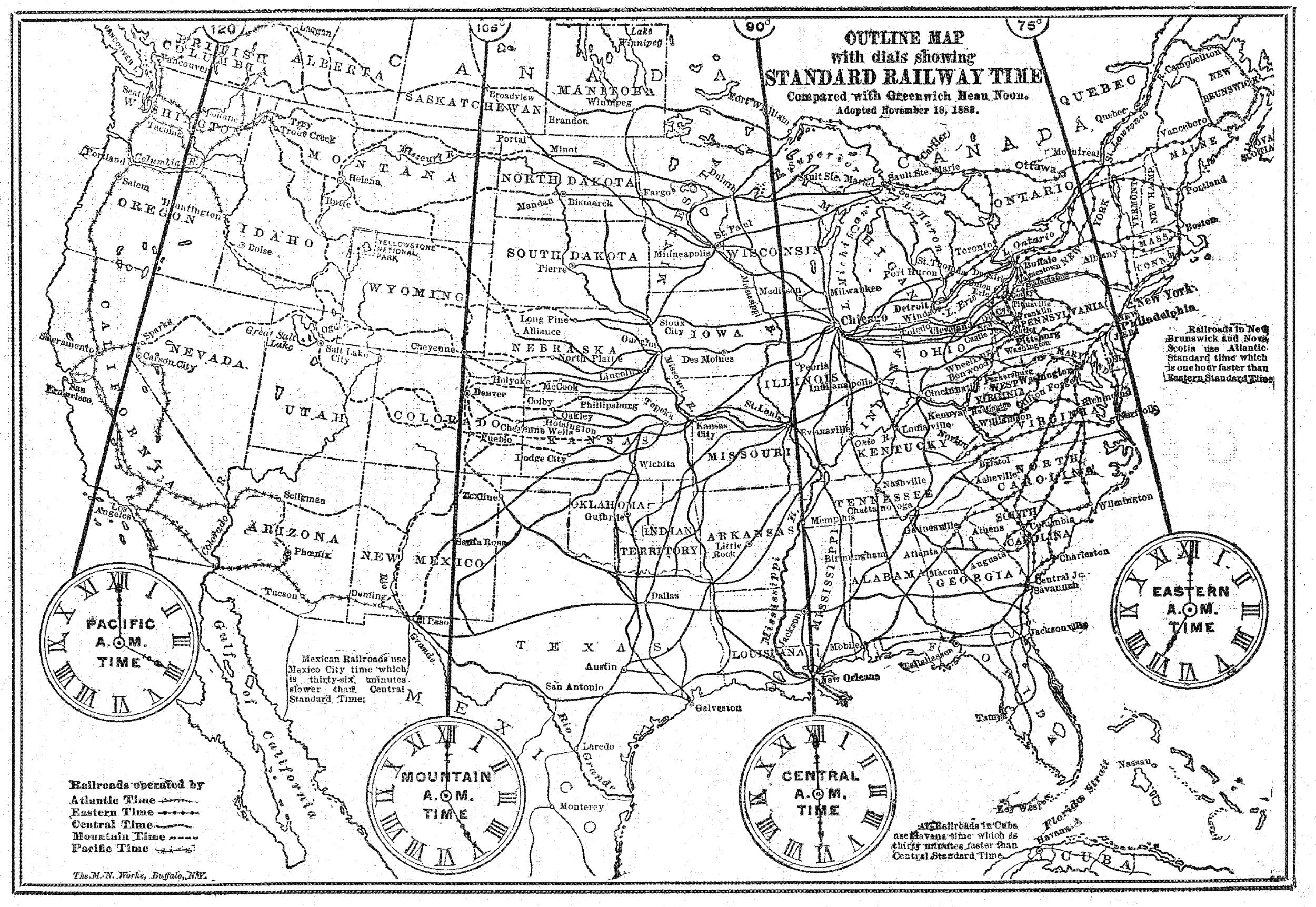

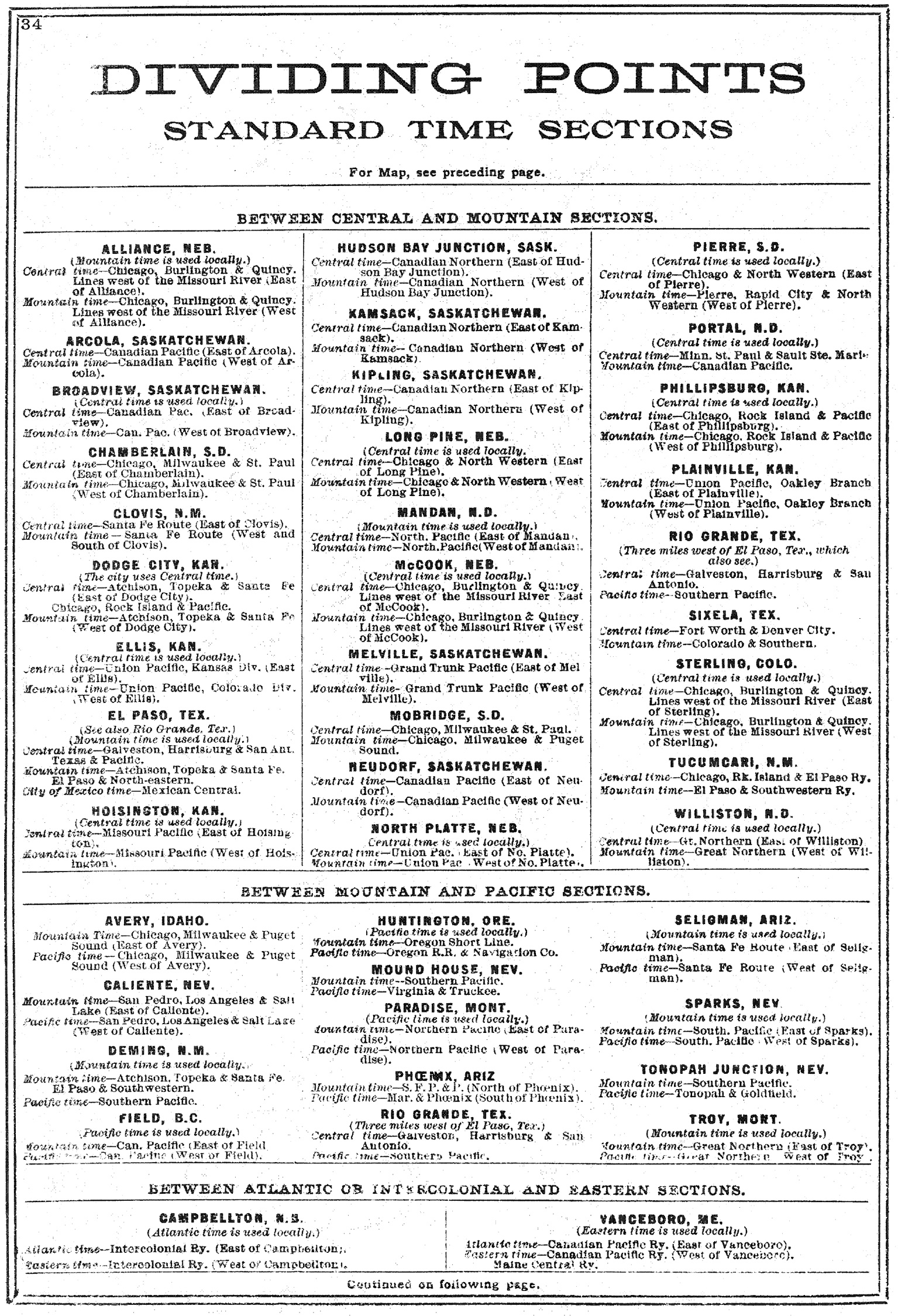

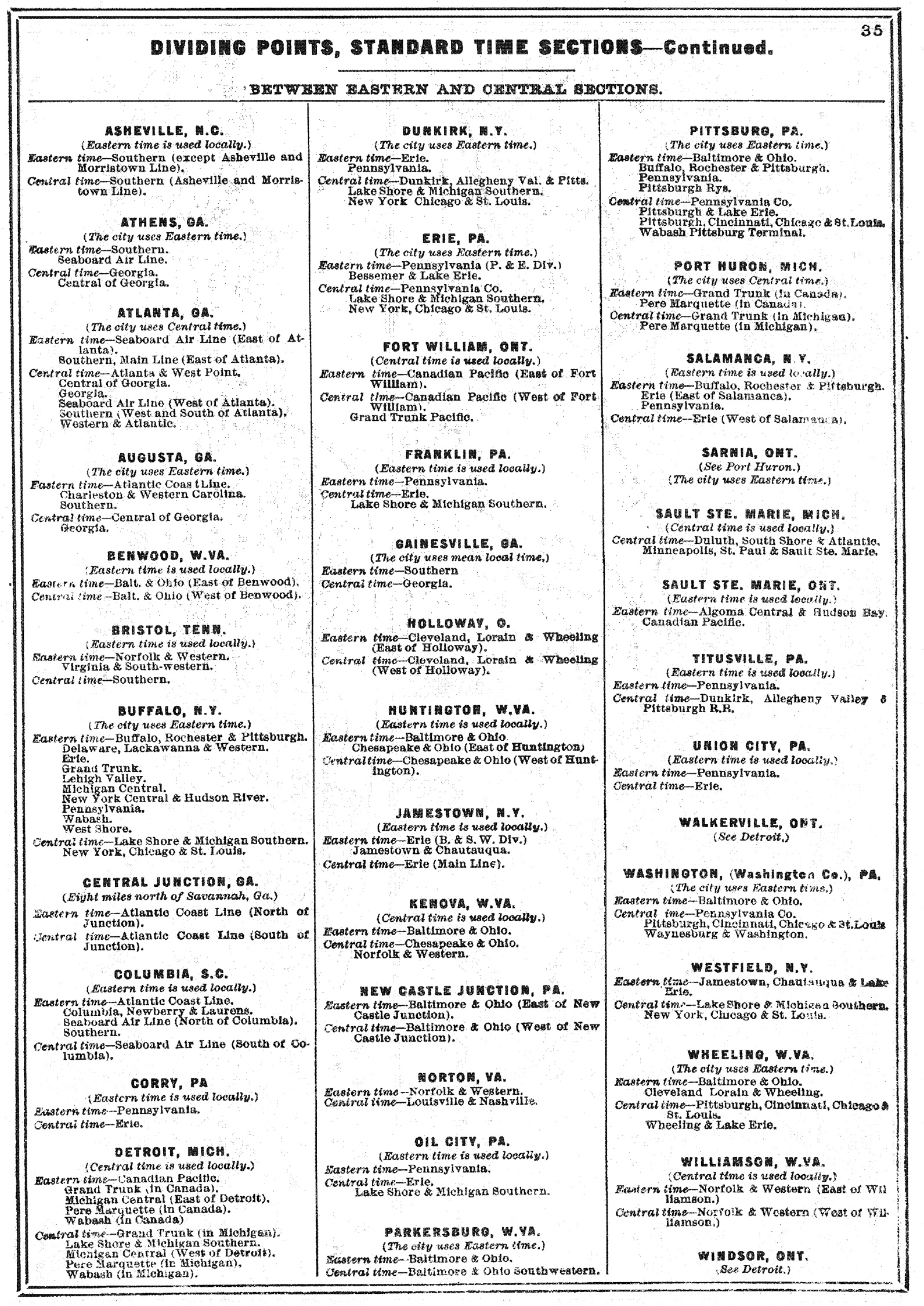

Standard Time Map

No other transportation mode could haul passengers and freight at such unparalleled speeds and in virtually any type of weather. As mentioned, railroads witnessed their greatest growth in mileage that decade by constructing more than 7,000 each year.

By 1890, the nation boasted a total of 163,597 miles. So much construction can be partially attributed to the strong economic times in which no financial panic occurred.

It could also be rightfully argued a great deal of overbuilding occurred as magnates like Jay Gould attempted to outmaneuver rival lines.

Kansas was a prime example. In 1890 it held the second greatest mileage by state, behind only Illinois, and would peak at 9,388 in 1920.

Although significant agricultural traffic partially explains the blanket of rails, corridors were sometimes built only yards or feet apart.

In the post World War II period, the economy could no longer support so many duplicate routes and there eventually abandoned (surprisingly, most remained in service until the 1970's).

Today, Kansas maintains less than 50% of its all-time high. A similar situation occurred in Iowa where it has lost more than 60% of its mileage (from 9,808 miles to less than 3,900 today).

Uniform Track Gauge

Perhaps the 1880s' greatest achievement was the adoption of a standard gauge; 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches. Railroads finally realized the only way to provide highly efficient service, and reap the greatest profits, was via a uniform gauge.

Differing gauges had persisted for decades. For instance, the Erie Railroad had long used a 6 foot gauge; the Pennsylvania Railroad 4 feet, 9 inches; and many railroad across the South went with a gauge of 5 feet. By 1890 virtually all of the country's major railroads operated with standard gauge.

It is somewhat surprising then that another gauge gained widespread support as the industry was adopting 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches. In the 1870's a narrow-gauge of 3 feet was argued by some as the ideal rail width for its lower operational and construction costs.

By the mid-1880s there was over 11,500 miles of narrow-gauge railroads. While much of this was used in branch line or industrial/short line operations, such as by logging companies, there was a growing contingent of common-carriers being built to 3-foot across the country, so much so that promoters nearly completed a transcontinental system.

The most famous narrow-gauge operations included the Denver & Rio Grande Railway; Denver, South Park & Pacific; Colorado & Southern; Toledo, Cincinnati & St. Louis; and Texas & St. Louis.

Widespread use of narrow-gauge systems was short-lived, however. According to Mr. Hilton's book it peaked in the 1880's (its peak year was 1886, showing 11,699 miles in service) before promoters sullenly realized that inefficient interchange, along with poor construction standards, made 3 foot railroads highly profitable.

Before 1920 less than half of the peak mileage remained, just 4,500; by the 1950 only 914 miles remained in use. Surprisingly, the D&RGW's San Juan Mining District survived until 1967 and another branch was not abandoned until 1980.

National Railroad Map (1889)

For the general public, rail gauge and the arguments thereof matter little; they were most concerned with improved comforts. By the 1880's services had improved drastically; virtually all of the modern-day conveniences were either in use or nearly so.

These included sleeping accommodations (provided by companies such as Pullman, Wagner, Woodruff, Flowers, and Monarch), lounges, parlors, and diners. The dome car would appear some decades later during the streamliner revolution.

Another important development was central steam heating, which did away with the dangerous use of wood or coal-fired stoves. These efficient method of keeping cars warm can be traced as far back as 1843 according to John H. White, Jr's book, "The American Railroad Passenger Car: Part 2."

Travel Improvements

Its first successful application, however, occurred in 1881 when a design conceived by James Emerson tested on several New England railroads that year.

He first attempted to use a boiler in the baggage car but this proved too dangerous when it nearly overheated.

He later conceived using the locomotive's own steam, with separate heaters under each car. It was a novel concept but a great deal more testing was be needed before it found use.

Other names important to its development included Lieutenant James W. Graydon, D.D. and J.H. Sewall, William Martin, and Edward E. Gold, all of whom continued to refine the concept.

Another important development was the "flameless," electric light. It first tested in 1881, a time which railroads were rapidly attempting to improve interior lighting due to public complaints.

Of course, the first cars to receive electric lighting were of the first class variety; Pullman and Wagner both had them featured on some of their equipment by 1886-1887.

One of the most important safety features came into use during 1887, the open-ended vestibule car, allowing guests to safely pass between cars. The need for vestibules became increasingly important with the introduction of services like parlors, diners, and chair cars.

According to his book, "The Railroad Passenger Car," author August Mencken notes it was the work of Henry Howard Sessions, the superintendent at Pullman, who conceived the vertical end frame, or friction plate, in 1887.

It had two primary purposes; to act as a cushion between cars and, more importantly, reduce the car's motion at each end. Another major event that into affect during the 1880s was the adoption of Standard Time zones.

The work is originally credited to Charles Ferdinand Dowd who was the first to propose a standard time within a pamphlet he published in 1870 entitled, "A System of National Time for the Railroads."

This piece became the basis for the industry's standard time. Dowd was an 1853 graduate of Yale University (boasting a doctorate) who believed the country should be divided into four sections.

These segments would cover 15 degrees of longitude, or an hour of real time. As the years passed the idea slowly gained traction although more than a decade would pass before it found widespread use.

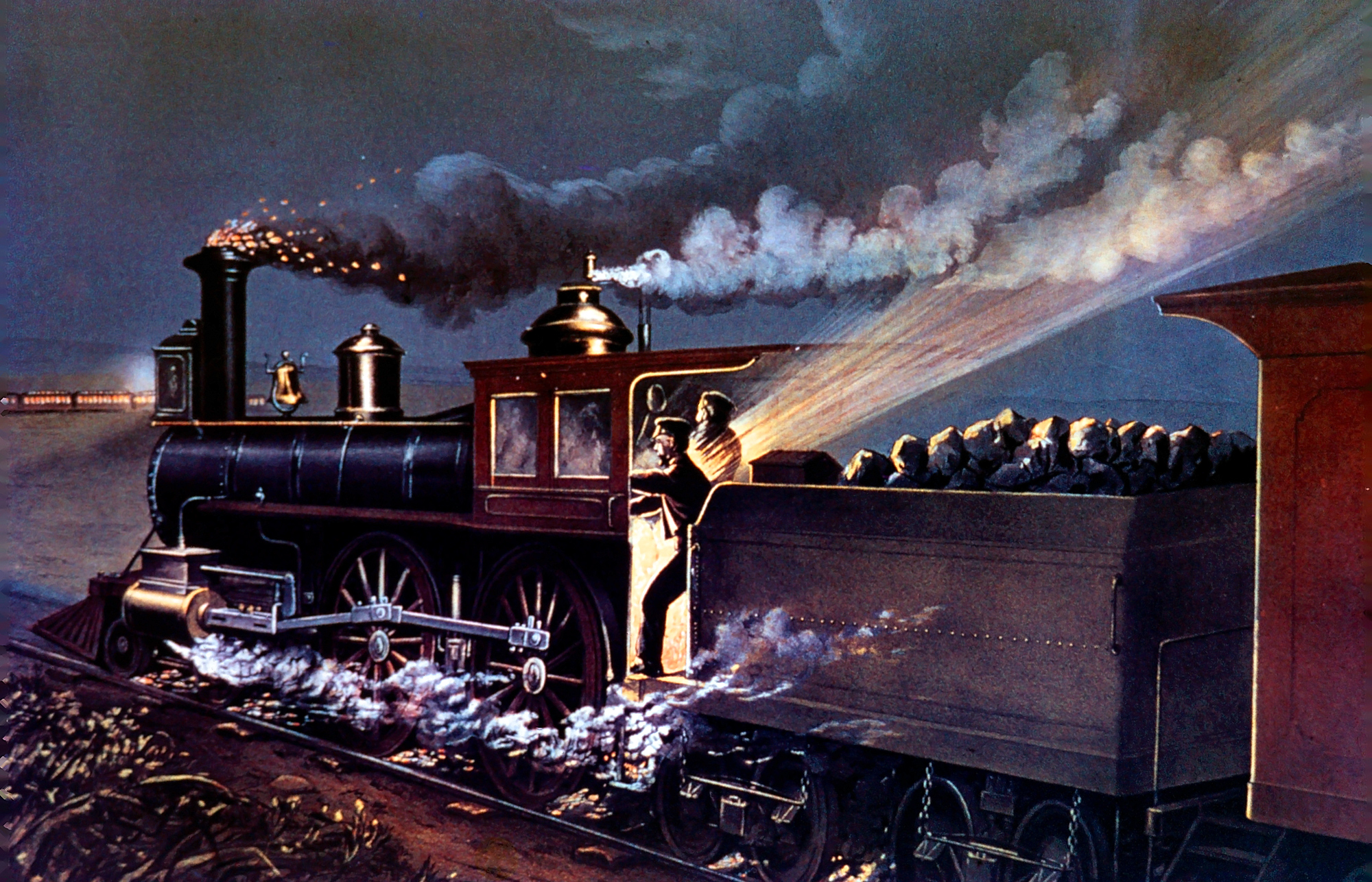

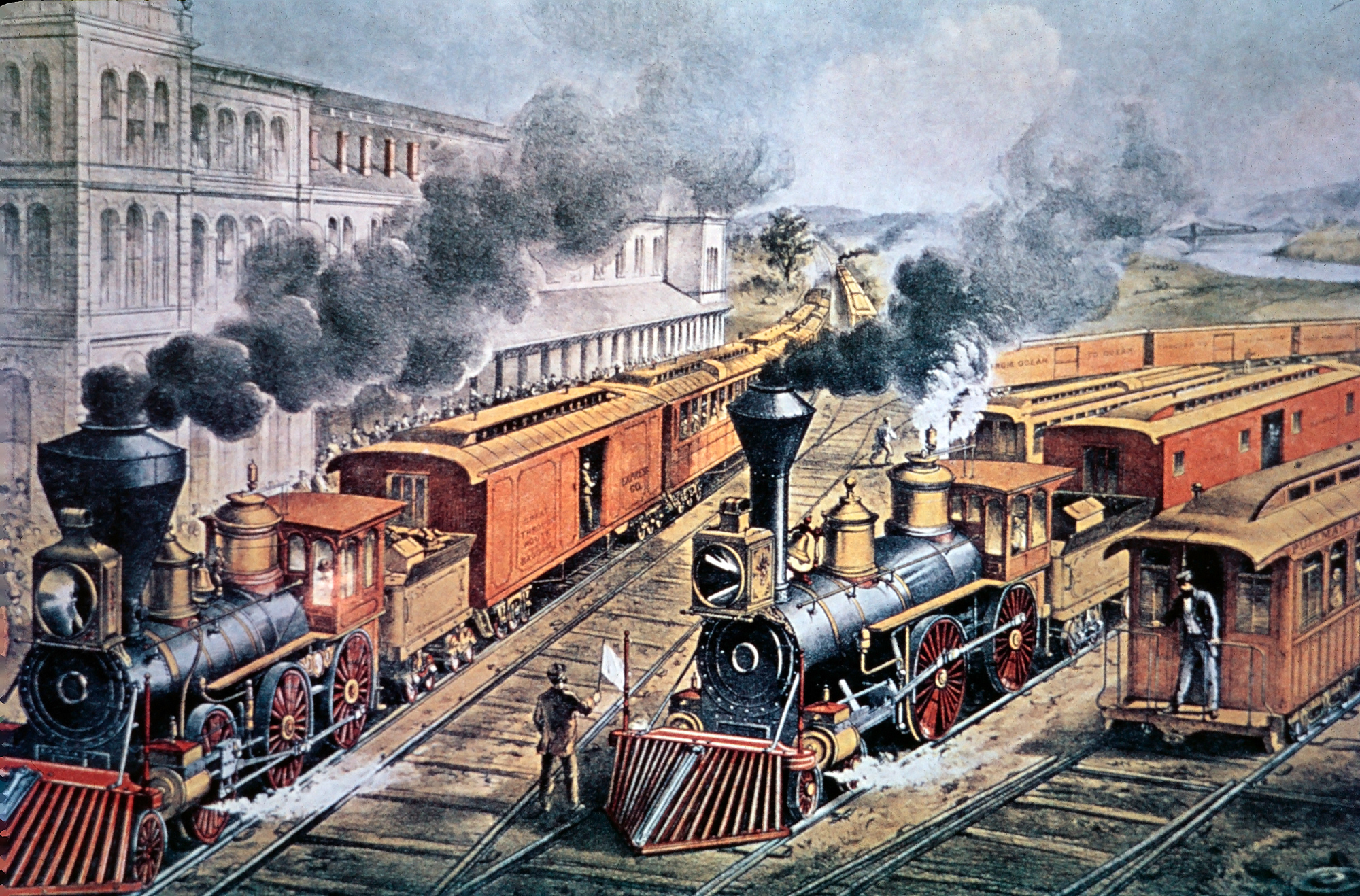

"American Railroad Scene. Lightning Express Trains Leaving The Junction." A Currier & Ives lithograph. American-Rails.com collection.

"American Railroad Scene. Lightning Express Trains Leaving The Junction." A Currier & Ives lithograph. American-Rails.com collection.Interstate Commerce Commission

Since the time could be different depending on where one was, along with the fact that it was earlier in the day the further west one was a plan was set in motion in the early 1870s to create a more unified timing system.

Originally known as the Time Table Convention, later as the General Time Convention. William Allen was secretary of the convention in 1876 and would be the one credited with planning the four major time zones now common in the country: Eastern, Central, Mountain and Pacific.

These zones lie along the 75th (Eastern), 90th (Central), 105th (Mountain) and 120th (Pacific) meridians. Railroads liked the new proposal and accepted it in 1883 with the new time going into affect on November 18th of that year. Rail construction in the 1880's slowed the following decade, largely due to the 1893's financial panic.

However, growth still ensued, particularly in the Midwest were the famed granger roads had taken root to serve America's Breadbasket. In 1887 the Interstate Commerce Commission was established, the first public agency put in place to monitor railroads.

The ICC's creation vastly improved safety standards, such as equipping knuckle couplers and automatic air brakes on all equipment. By the early 20th century, federal oversight was firmly established.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Discover Scenic South Dakota: Train Rides Await!

Feb 23, 25 12:15 AM

Although more than 52% of the state's railroads are abandoned today, there are train rides available in South Dakota! In addition, a museum in Hill City, home of the Black Hills Central Railroad, offe… -

Dine in Style: Experience Ohio's Culinary Train Journeys

Feb 22, 25 11:23 PM

Discover where scenic dinner train rides can be found in Ohio here, a state steeped in rail history. -

Riding the Rails: Oklahoma's Unforgettable Train Rides!

Feb 22, 25 11:18 PM

Currently, the Oklahoma Railway Museum is the only location within the state hosting public excursions. Find out more about it and all of the state's museums here.